It was a day just like any other at the City Archives. Archivists and researchers spoke in whispers as they gently leafed through decades-old memoranda and Kodachrome photographs. Just then, at the front desk, a mysterious stranger appeared with a hard drive and a look that said she wanted to donate it. When she couldn’t answer how much data was on the drive or how it was formatted, it was clear that this day would not be normal after all and… it would not be easy.

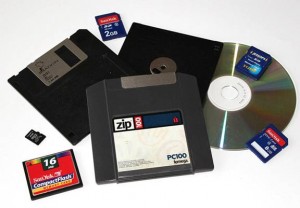

Archives Manager Heather Gordon likes to say that being an archivist is like “playing detective”. There has always been an aspect of detective work in what archivists do—from digging through boxes left abandoned in a garage searching for records to helping researchers find the documentation that helps them accomplish their work. In the age of digital acquisitions, her statement couldn’t be more true. Unlike their physical analogue counterparts, donations that come to us in folders on digital media can’t be easily leafed through and assessed at first glance. Those folders and their contents are made of bits that don’t have meaning without some kind of hardware and/or software intermediary.

BitCurator

This past weekend, thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, I was fortunate to travel to the University of Maryland just outside of Washington, DC, to participate in the Professional Experts Panel of the BitCurator Project. BitCurator is a response to the needs of archivists who need to securely acquire and assess digital acquisitions before they are processed and made available to the public. Law enforcement agencies have been collecting evidence from digital media for many years and an entire discipline has sprung up as a result. Digital forensics experts recover digital evidence used in investigations and prosecution of crimes.

Since the discipline’s inception, digital forensics experts have primarily used proprietary software tools in their work. However, in recent years, leaders in the field have been working to develop open source tools with functionality that can compete with, and sometimes even surpass, their proprietary counterparts. In fact, as digital forensics expert Brian Carrier says on his blog, “Open source tools may have a legal benefit over closed source tools because they have a documented procedure and allow the investigator to verify that a tool does what it claims.” Significantly, his reasoning is the same that led the City of Vancouver Archives to select open source software for processing of digital materials—we have to be able to show our work at every stage so researchers can be assured that the archives are authentic.

The open source tools currently available were made for digital forensics experts, so they can be difficult to navigate for even the most technically savvy archivist. BitCurator aims to make these open source digital forensics tools understandable and usable for archivists. The output of the tools will be used to usher the digital records through archival processing and prepare them for use.

Low-risk data extraction

BitCurator hopes to help archivists safely extract data from physical media. Simply plugging in media can cause data loss and corruption, but there are forensically sound methods for connection and extraction like using physical write blockers and forensic imaging. No matter what state a device is in when it arrives at the archives, if we have the right attachment on our write blocker, we can hope to salvage the data.

Analyzing the data

Once we have the data extracted, BitCurator tools will help us analyze it and prepare it for processing and, ultimately, access. The kinds of functions that the tools will add to our digital curation workflows include the following:

- Identification and redaction or protection of private and sensitive information

- Repair of damaged files and filesystems

- Recovery of accidentally deleted or hidden data

- Generating logs of extraction and analysis activities

- Identification of files types and sizes

A good example of when such tools might be useful is a donated computer from a business that has closed down for good. Archivists should be able to use the BitCurator tools to image the hard drive of the computer securely and find out what kind of software and records are stored on it. Additionally, we can identify and protect any sensitive records that should be restricted in our reading room, like social insurance numbers and home addresses.

The end goal is to have tools that produce a digital transfer package from raw digital acquisitions on almost any media. Then, we can process that package using our new digital archives system and provide the records to the public with the confidence that they have been handled securely and are what they purport to be.

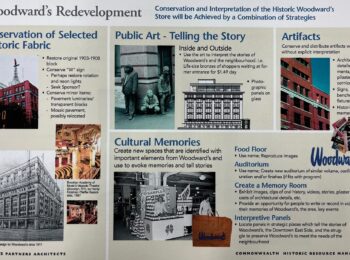

GROUP PHOTO ABOVE of BitCurator Project Team and Professional Experts Panel: L to R: Kam Woods (Postdoctoral Research Associate in the School of Information and Library Science at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.), Jeremy Leighton John (Curator of eMANUSCRIPTS and Scientific Curator in the Department of Western Manuscripts at the British Library), Erin O’Meara (Electronic Records Archivist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Gabriela Redwine (Archivist and Electronic Records/Metadata Specialist at the Harry Ransom Center), Leslie Johnston (Manager of Repository Development in the Office of Strategic Initiatives at the Library of Congress), Christopher “Cal” Lee (Associate Professor at the School of Information and Library Science at UNC, Chapel Hill), Bradley Daigle (Director of Digital Curation Services and Digital Strategist for Special Collections at the University of Virginia Library), Porter Olsen (back) (Research assistant, MITH), Erika Farr (Coordinator for Digital Archives in the Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University), Matthew Kirschenbaum (kneeling) (Associate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Maryland and Associate Director of the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities), Michael G. Olson (back) (Manager of Digital Projects for Stanford University Libraries), Alex Chassanoff (Project Manager, UNC SILS), Susan Thomas (Digital Archivist for the Bodleian Library’s Western Manuscripts department), Naomi L. Nelson (Director of the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library at Duke University) and Courtney Mumma.

Its takes years to learn forensics. There are specialities like mobile and soon big data forensics. How did you archive the Vancouver Riots? Police can barely manage the data flow for the riots. How can archives with small budgets? Trying to archive digital media? Most data is on hidden in the deep web. Have you figured out how to get data from companies like Google and Facebook? http://facebookjustice.wordpress.com/2011/08/30/did-police-mishandle-the-riot-evidence-new-website-suggests-so/

Archivists working with digital forensics tools don’t have delusions about becoming forensics experts and our goals are different from those of police services. We do acknowledge, however, that the tools could be very useful towards preserving and providing access to historically valuable archives.

Regarding your questions about the riots and data in the deep web, City of Vancouver records make their way to the Archives once their active records retention periods have expired, usually years or decades from the date of creation. Private-sector records are donated to us by citizens and appraised by archivists to determine whether they have archival value. So far, we haven’t had any acquisitions related to the Stanley Cup riots of 2011. We would not attempt to uncover “hidden data” from the deep web or from any source that is not expressly part of a donation that we have been given permission to analyze.

looking for archives on orphanages of early 1900s there was one on penticton and wall street which is now demolished to a park

In 1892 the Women’s Christian Temperance Union opened a home for motherless children in Vancouver, known as the Protestant Children’s Home. The organization was later incorporated as “The Alexandra Non-Sectarian Orphanage and Home for Children” and moved to Alexandra House in Kitsilano. The orphanage was closed in 1938. The Alexandra Neighbourhood House fonds (AM420) located at the Archives includes minutes, financial records and photographs of the orphanage. Descriptions of this material can be accessed through the Archives’ website.

I saw the records in the archive you mentioned of the Alexandra orphanage, but are there any records anywhere of the children who were in it? My great grandfather and his siblings were in that orphanage. I’m doing our family tree and we have no idea who his parents were. Thank you

Some of these records in BC Archives might help: http://ht.ly/R4pQM, in particular this series: http://search-bcarchives.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/admissions-case-files. There could be privacy restrictions on the file you’re looking for, though, depending on the age of your great grandfather or his death date.