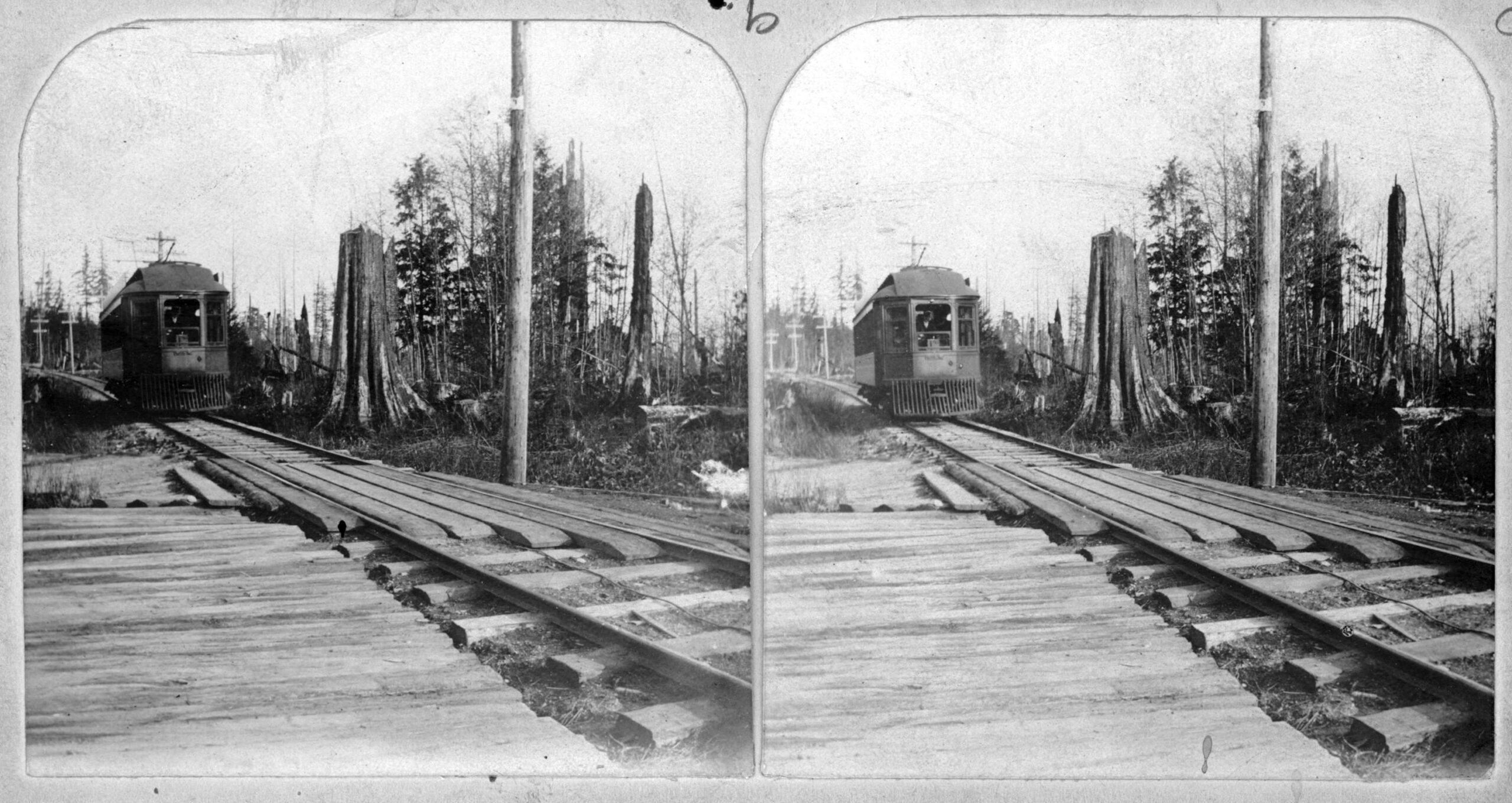

Stereoscopic photographs, a way to view scenes with a three dimensional effect, exploded in popularity in the 1850s. Images documenting life and scenes from around the world were mounted on stereo cards, which could be purchased and added to a collection. In the 1800s, these cards were often viewed at gatherings in sitting rooms as a form of entertainment. The three dimensional quality of the images gave viewers the sense that they were immersed in the scene.

Stereoscopic images are created using a camera with two lenses set horizontally apart at a width about equal to a person’s eyes. Two photographs are exposed simultaneously through the lenses, creating two separate frames that have slightly different viewpoints. These individual images were either printed and mounted on cards and viewed with a stereoscope, or mounted in specially-created slide mounts that hold two frames, which are viewed by projection.

Stereoscopes are simple instruments used to view stereoscopic images. They have two identical lenses spaced apart at the same width as a person’s eyes, and have a holder in which to set the stereo card so the left image is seen with the left lens and left eye, and the right image is seen with the right lens and right eye. When the two images are viewed through a stereoscope, the eyes are made to look at the left and right images independently. Since most people have binocular vision, the two images are brought together in the brain creating single image with dimension and depth.

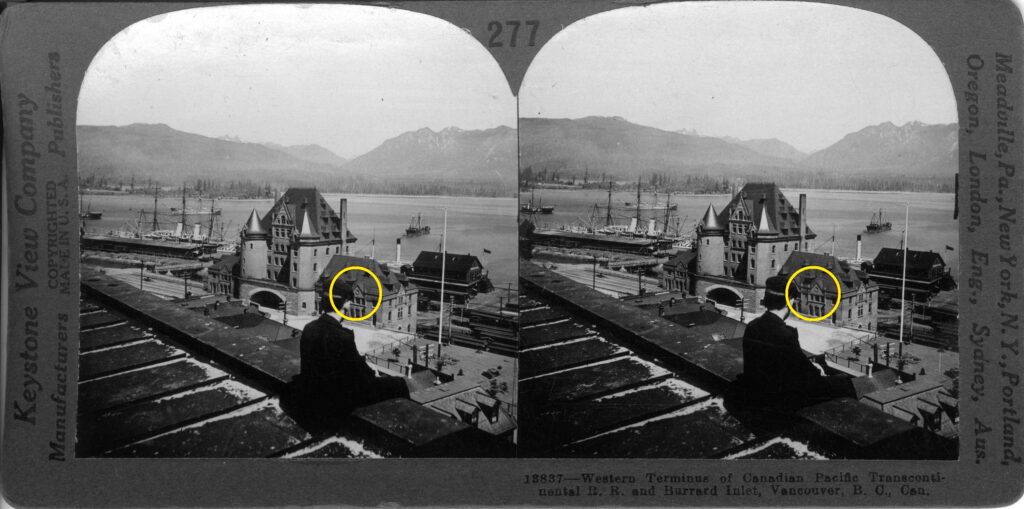

Two stereographic images viewed without a stereoscopic viewer often look almost identical and lack depth. However, a closer inspection will usually identify the images as stereo pairs rather than duplicates of the same image. Closer inspection usually involves looking for an object that is just in front of something more distant behind it, and seeing if there is a difference in where the object in front touches the object behind. In the left image, the near object will look further to the right in comparison to the background, and vice-versa with the right image. There may also be differences in the details visible in the left and right edges of each image. However, unless it is a negative being viewed, the printed version may be cropped, and therefore the differences between the edges of both images may be somewhat deceiving.

The degree to which a three-dimensional effect is achieved with stereograph images depends on the scene itself. Scenes composed of subjects in the foreground, middle and background will have a greater three-dimensional effect than scenes that show mainly distant objects or landscapes. However, a greater depth, and therefore three-dimensional effect, can be achieved in the latter type of scene by using two cameras with identical lenses separated at a greater distance than a person’s eyes. The extra distance between the lenses creates two points of view with more obvious differences in perspective. This technique is known as hyper stereo.

Stereo cards were produced into the early 1900s but their popularity was waning. There was a resurgence in the popularity of stereograph photography in the mid-1940s, when the David White Company started to manufacture the Stereo Realist camera. This camera used 35mm film and was accessible to amateur photographers. Other manufacturers followed suit, producing similar cameras, as well as offering slide mounting services, stereo slide viewers and stereo projectors for the viewing of the stereoscopic photographs. These 35mm film cameras were usually loaded with slide film. After exposure and development, the left and right images (i.e. transparencies) were mounted side by side in a single glass or cardboard mount.

The Archives has a number of different examples of stereoscopic photographs in a variety of formats.

James Crookall stereoscopic photographs – Nitrate Negatives

James Crookall (1887-1960) was an avid amateur photographer who had a career with the Union Steamship Company of B.C. and served in World War I for two years with the Royal Flying Corps. The James Crookall fonds contains approximately 4,000 photographs, of which there are 131 stereoscopic photograph pairs. These stereoscopic pairs were taken by Crookall in the 1920s and 1930s, and depict areas of the Pacific Northwest and Vancouver.

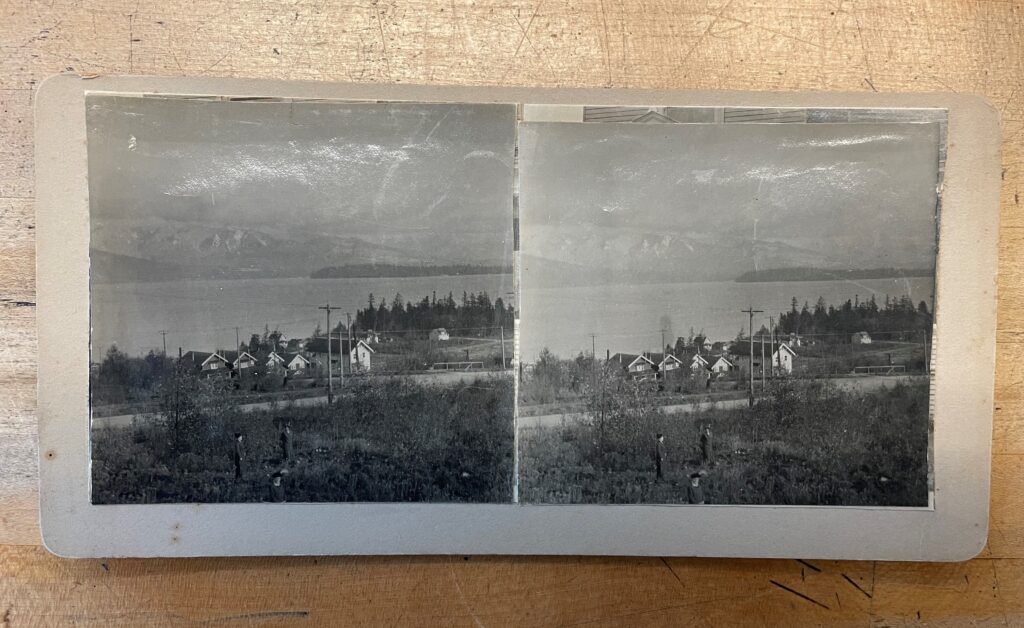

Crookall’s stereo images were shot using a medium format stereo camera on nitrate base negatives. The negatives are uncut. The 121 stereographic pairs in the Archives’ holdings would likely have been printed as individual images to be mounted on a card for stereoscopic viewing. The scans of each negative show two images side by side with a numeric code between them. When viewing the scan, the image on the left is actually the view from the right lens of the camera, and the image on the right is the left view. This is most easily detected when comparing a very close object and its relationship to a very far object. The negatives or prints would have been cut and switched for correct viewing in a stereo viewer.

Handmade stereo cards

Stereo cards for use in a stereo viewer were a fairly standard size of 7” wide by 3.5” tall, and when placed in the stereo viewers, the images could easily be seen by each eye. People made stereo cards themselves by gluing two prints onto a card. The prints were either a proper stereographic pair from a stereo camera negative or occasionally two prints from the same image. One example in the Archives’ holdings shows the reuse of a stereo card (AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-2292), where a set of images has been pasted over another set of images, giving this stereo card a distinct handmade quality.

Stereo cards were commercially made beginning just after the mid-19th century. They included images of distant places, scenes of cities and landscapes, and scenes of everyday life from various cultures and classes of society. There were also series that told stories through a progression of scenes. Some of the big companies producing stereo cards were Underwood and Underwood, The Keystone View Company, and the London Stereoscopic Co.

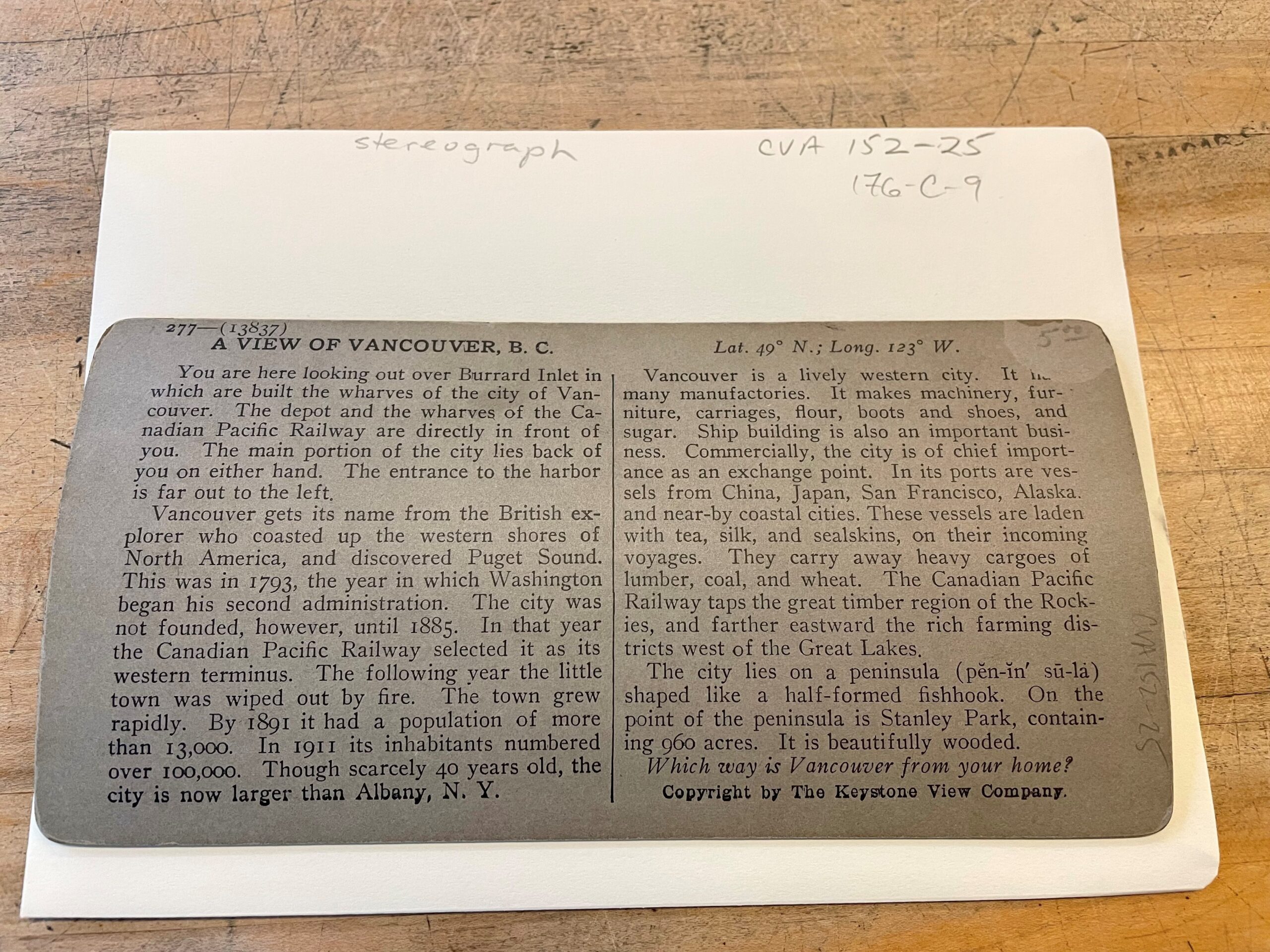

Commercial cards usually have the name of the company printed or embossed on the card, as well as an image number and title. Some have more descriptive information about the image. Some include historical or educational information for the viewer to read.

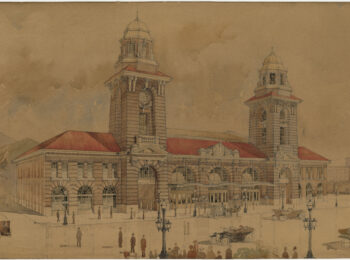

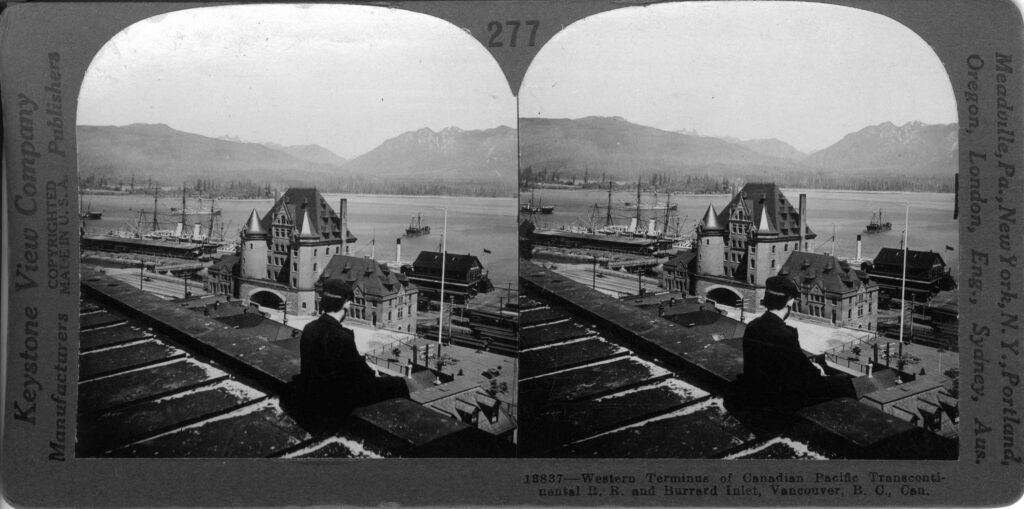

An example of such a stereo card is this card, shown above and below, which was produced by the Keystone View Company. The images are mounted onto a curved card. The title and view number were embossed, while the company name and information were printed on the card. The back of the card is filled with text describing the image and informative details about then present day Vancouver.

Another example of a commercially produced stereo card is this one (AM336-S3-2-: CVA 677-780, shown at the top of this post and below) from Timms’s Stereoscopic Views, where instead of printing the images, cutting them, and then mounting them on a card, the images have been directly printed as a full silver gelatin print in stereo card size.

Glass Stereo Negatives

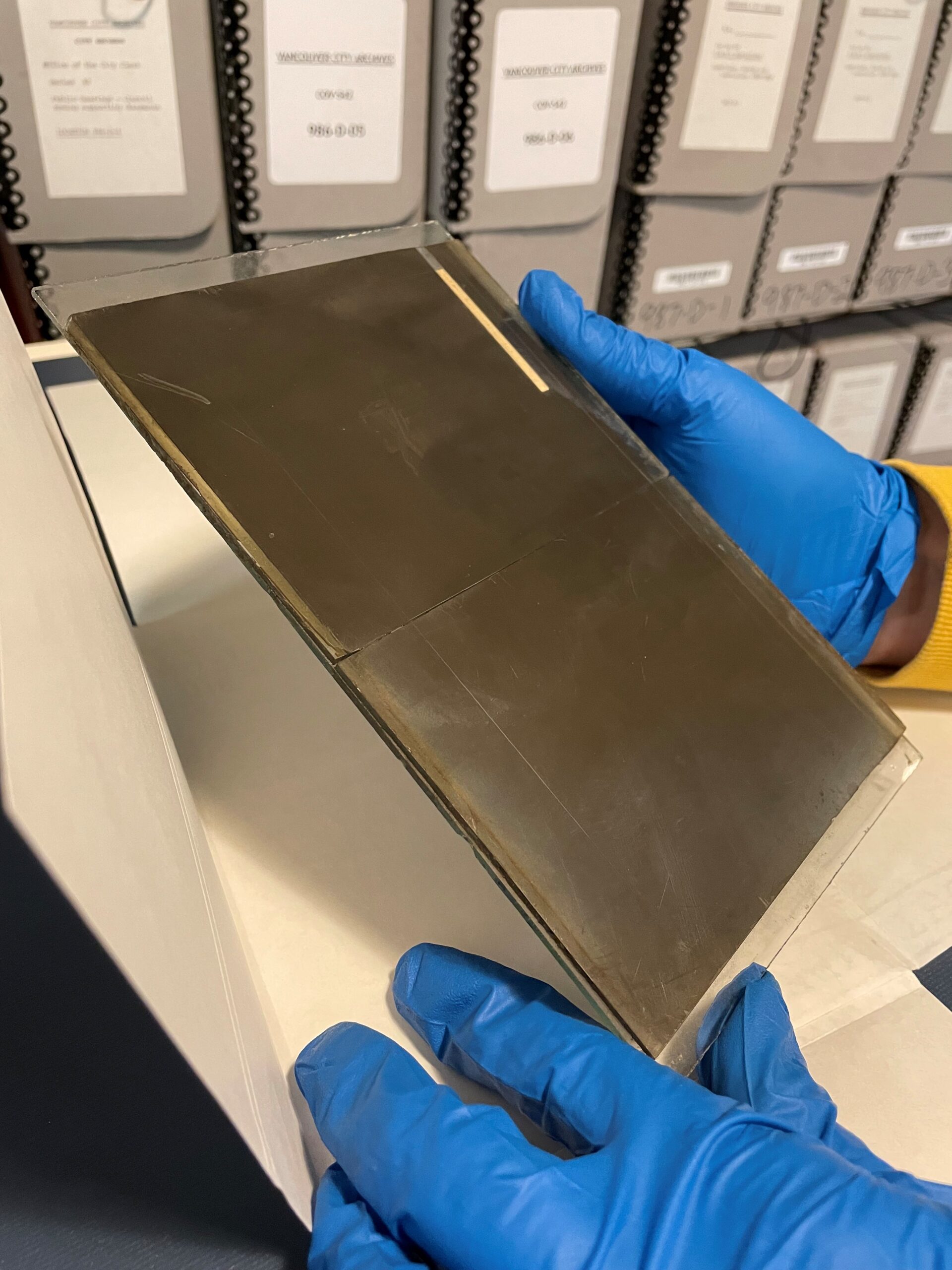

Some stereo cameras used glass plate negatives, generally with a glass plate size of 5”x8”. Here is an example of a stereographic pair on a glass negative that has been cut in half and glued onto a support glass plate in the correct orientation for stereo viewing. This was likely done on purpose, and would have made printing on one piece of paper easier.

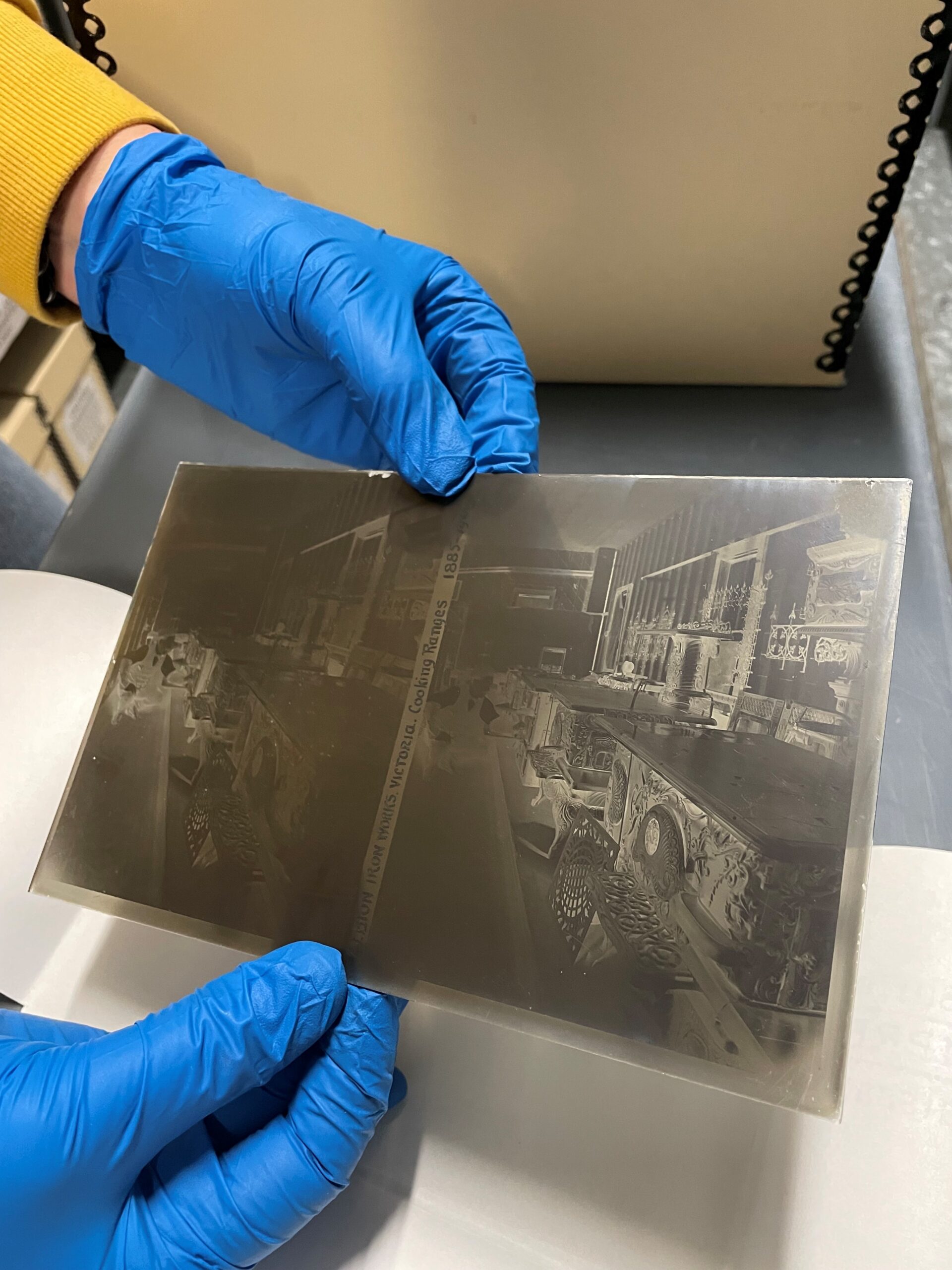

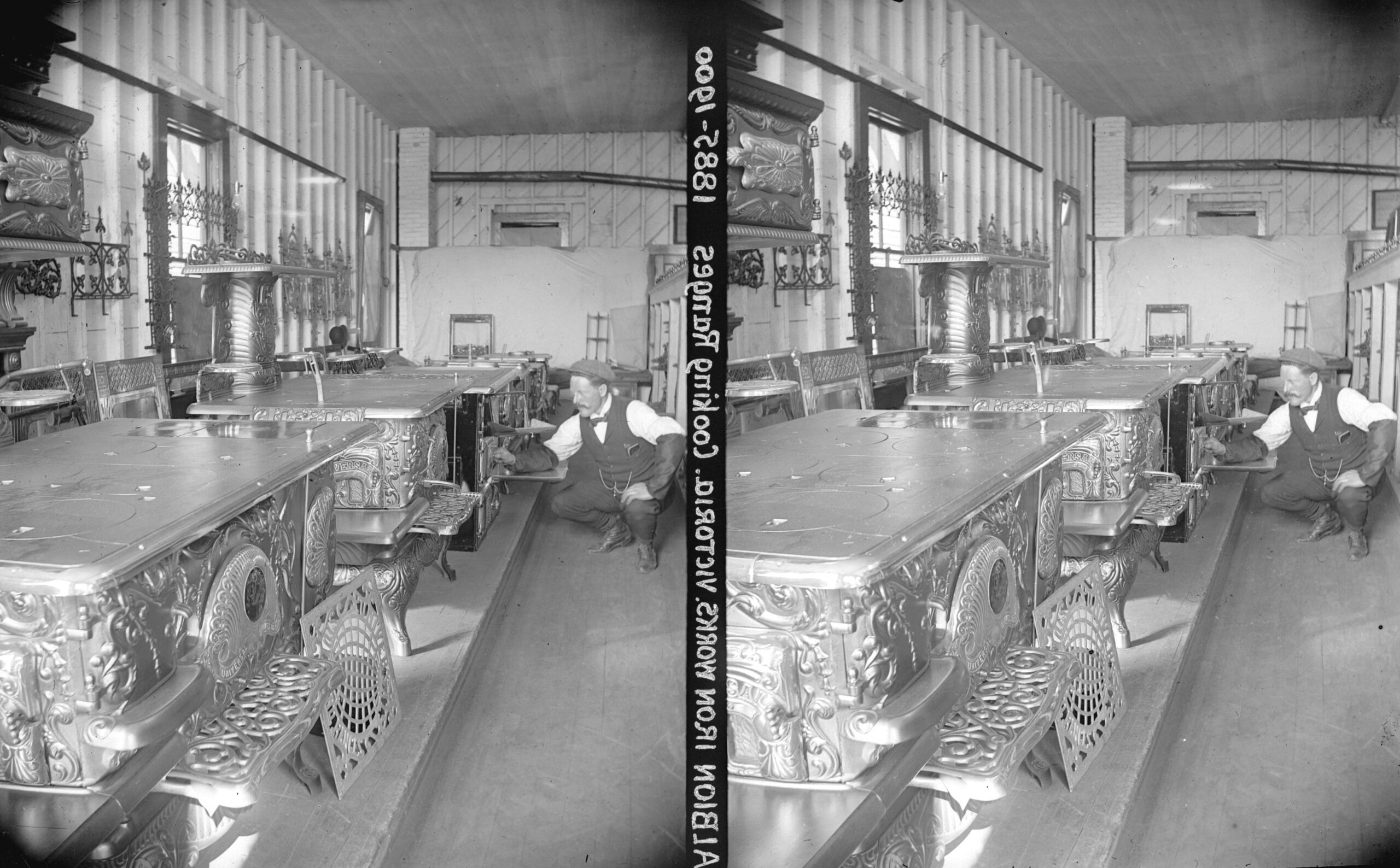

Below is an example of an uncut glass negative. The photographer has inscribed the title and notes between the frames. When printed, the images would need to be transposed in order to produce a proper stereographic pair. If they were not, which is how they appear in the scanned version below, they would be known as a pseudoscopic.

Mounted positive transparencies as stereo views

A number of 35mm and medium format stereo cameras were made starting around 1949 when the Stereo Realist camera came out. Most of the images were square format on 35mm film. This camera made stereo popular again after stereo card interest waned in the earlier part of the 20th century.

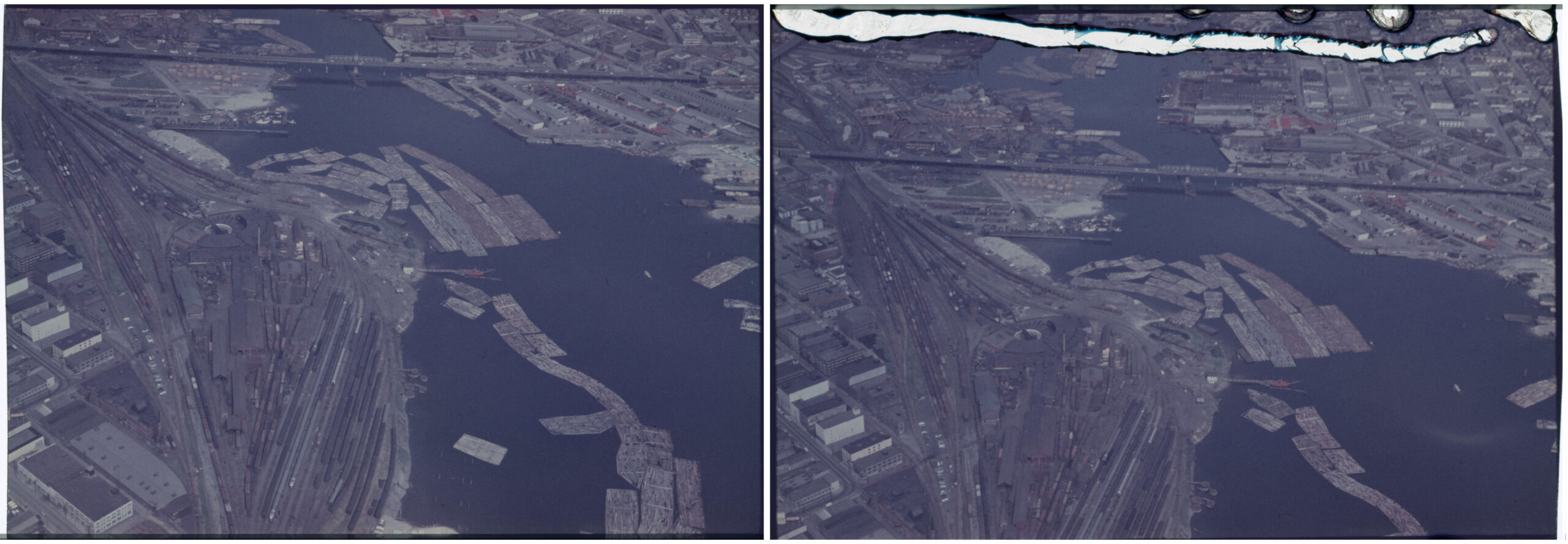

The Archives has a number of aerial photos that are are mounted in the 35mm stereo mounts, but it is likely that these particular aerial stereographic pairs were shot with a regular 35mm camera, with two images taken at spaced intervals from a moving plane. This is evident in that the vertical alignment of some of the images is way off. These aerial views do not have much of a three dimensional effect with everything at a pretty equal distance away.

Here is an example where it is obvious that the image pair were not taken with a stereo camera, as the bridge does not line up properly.

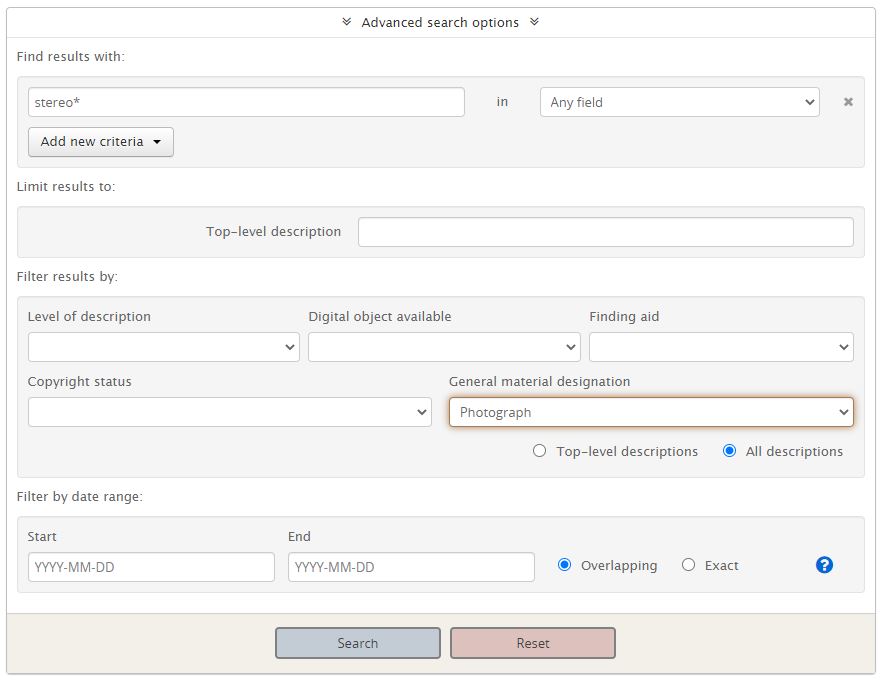

If you would like to see more of the stereographic photographs in the Archives’ holdings, you can do so by searching our database. Go to the Advanced Search page, and enter the search term “stereo*”. Also select “Photograph” from the drop down menu under “General material designation”, then click “Search”.

Editor’s note: Kathy Kinakin, the primary author of this post, is a long-time volunteer at the Archives, and also worked here as an auxiliary conservator in 2017-2020. She holds an MA in Photographic Preservation and Collections from Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson).