This is the second post related to the City of Vancouver Archives’ current student exhibition on display in the Archives’ gallery space. Curated by Camryn Traa, “Otter Moments” explores the strange and sometimes surprising connections between sea otters and Vancouver. Check out the previous post, Part I.

Spurred on by the Pacific maritime fur trade and the demand for their thick coats, sea otters were hunted to near extinction in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In British Columbia, where sea otters had become locally extinct, a joint federal and provincial project in 1969 strived to reintroduce the species to the province. The Fisheries Research Board of Canada and the B.C. Department of Recreation and Conservation planned to transplant 30 sea otters from the Aleutian chain of islands in Alaska to a location on the coast of Vancouver Island. Transporting any animal over a long distance poses risks, but 29 of the original 30 sea otters survived the move. More were sent in following years to help the population grow, and otters were also moved to locations along the coast of the United States.

The biologists who organized the transplant originally prepared to move the sea otters to their new home by boat. In a change of plans, the United States Atomic Energy Commission––the American government agency responsible for the study of nuclear energy––instead airlifted the otters. This shortened the sea otters’ time in captivity and increased their likelihood of survival.

Why was the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) involved in the translocation of sea otters? During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a nuclear arms race. In the 1960s, the AEC chose Amchitka, one of the Aleutian Islands, as the site for the underground testing of anti-ballistic missiles when their bombs became too big to be safely detonated at their existing test site in Nevada. Since testing posed a lethal risk to the sea otter population in Amchitka, a portion of the local otters were evacuated prior to the nuclear tests.

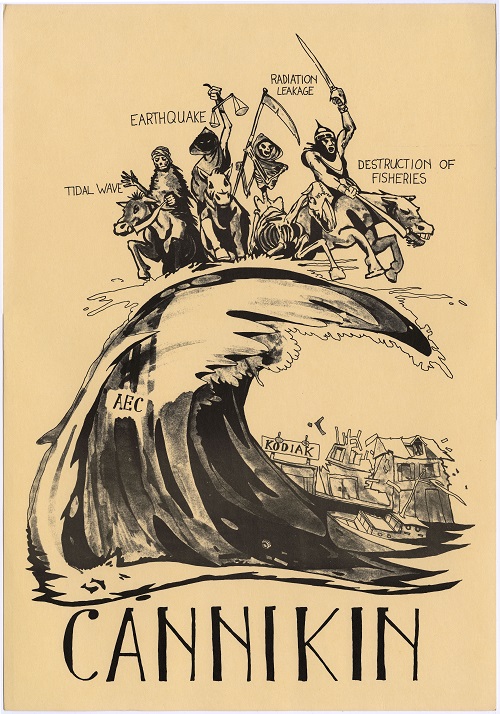

The nuclear tests in Alaska sparked public outcry. In 1964, Alaska had suffered an extremely powerful earthquake that killed over 100 people and caused massive damage. People along the west coast of North America were concerned about the underground explosions triggering another earthquake and tsunami, as well as the risk of radioactive pollution and habitat destruction. The AEC tested nuclear weapons on the remote island of Amchitka in 1965 and 1969, but it was the 1971 testing of the anti-ballistic missile, code-named Cannikin, that caused the most concern because of its large size. With a yield of 5 megatons of TNT, Cannikin was the largest underground bomb the U.S. ever tested.

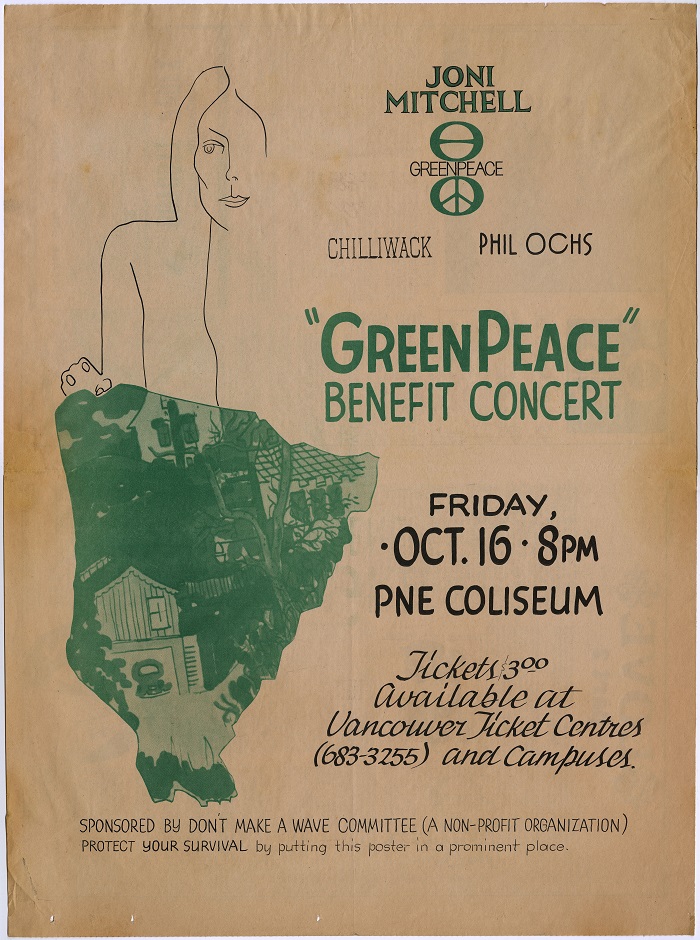

In Vancouver, protests were held outside the U.S. embassy, petitions called on the Canadian government to take more drastic action against the tests, and protesters blocked the Canada-U.S. border, shutting it down for an hour. The slogan used on banners––“don’t make a wave,” in reference to the threat of a tsunami––became the name of a Vancouver organization campaigning to stop the tests.

The Don’t Make a Wave Committee, made up of local activists, ecologists, and journalists, chartered the fishing boat Phyllis Cormack to sail with a crew of twelve to Alaska to interrupt the tests. They renamed the boat Greenpeace I. Although the activists aboard the Greenpeace I were ultimately forced to turn around and Cannikin was deployed on November 6, 1971, the expedition sparked widespread support for the anti-nuclear movement. The Don’t Make a Wave Committee later changed its name to the Greenpeace Foundation. Greenpeace has since grown into an international organization and undertaken numerous environmental campaigns.

Today, the sea otter population in British Columbia numbers over 7,000 and they are thriving on British Columbia’s coast, but this is not the end of our story. The 1969 otter translocation occurred without consulting First Nations. Sea otters are a keystone species, meaning their presence shapes their entire ecosystem, and they can eat up to a third of their body weight a day in shellfish. By preventing the overpopulation of sea urchins that eat kelp, sea otters enable the growth of important kelp forests. While this is good for the environment, sea otters and their massive appetites have also impacted the First Nations dependent on the same shellfish. With the population growing larger than their food supply, sea otters have spread to new territory and threaten the seafood that communities depend on. To navigate the changes returning sea otters bring with them, Indigenous leaders, knowledge holders, and scientists are working on collaborative projects like Coastal Voices, which aim to help communities develop ways to manage the sea otters’ impact.

While the sea otter now thrives on B.C.’s coast, these furry creatures’ turbulent history and complex present are still intertwined with Vancouver. To discover more strange and surprising ways that sea otters are woven into the city’s history, visit the Otter Moments exhibition at the City of Vancouver Archives.

Editor’s note: The Archives’ gallery at 1150 Chestnut St in Vanier Park is open Monday-Friday, 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM. We encourage you to check out the exhibit in person!