This weekend, July 8th-10th, is the Summer Live event at Stanley Park’s Brockton Point. In celebration of Vancouver’s 125th birthday, Summer Live will exhibit the city’s diverse arts and culture, showcasing artistic workshops, dances, performances and art installations. It will be a celebration of what Vancouver has become in all its 125 years, including:

- stories and drum songs by members of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations,

- Coast Salish canoe races in Coal Harbour,

- free performances by internationally-renowned musical acts, and

- recreational and family activities on the Brockton Point fields.

An Untouched Landscape Despite Be-Ins, Murder and Banks Heists

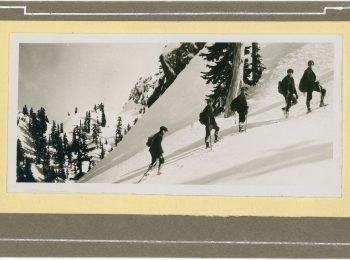

While Vancouver’s skyline has changed somewhat over 125 years, Stanley Park’s natural landscape – with the exception of the odd wind storm – has remained relatively unscathed since the city’s beginning in 1886. The park continues to be the city’s natural fixture. When you are at Brockton Point this weekend, stroll along the seawall or through the trails and appreciate the park’s history.

Many events have taken place in Stanley Park since its beginnings, and thanks to Major Matthews and his habit of collecting, numerous newspaper clippings documenting these events have been kept. They can be a very valuable resource when the Archives does not have a record of these events in any other form.

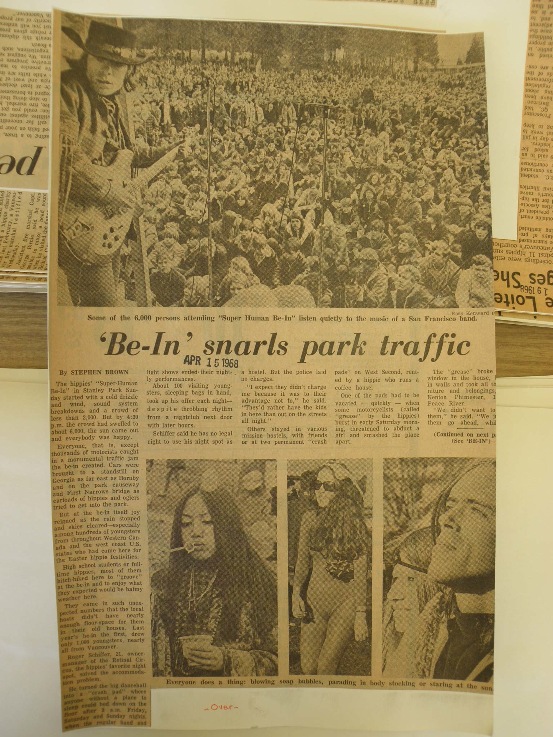

Traffic has always been heavy on the Stanley Park causeway during rush hour. If you’re attending this weekend’s festivities, hopefully you can avoid this. During the late 60s, though, traffic jams could have been due to factors other than vehicle volume. The place to come for be-ins, Stanley Park was where you could commonly see those people to whom many referred as “hippies”. In April 1968, for instance, a “Superhuman Be-In” attracting hippies from western Canada and the United States’ west coast caused traffic to stand still on Georgia to Hornby, and from the Lions Gate Bridge through the park causeway. According to Matthews’ collection of clippings, be-ins were around in Vancouver as early as 1967, and were very common at Stanley Park during this period.

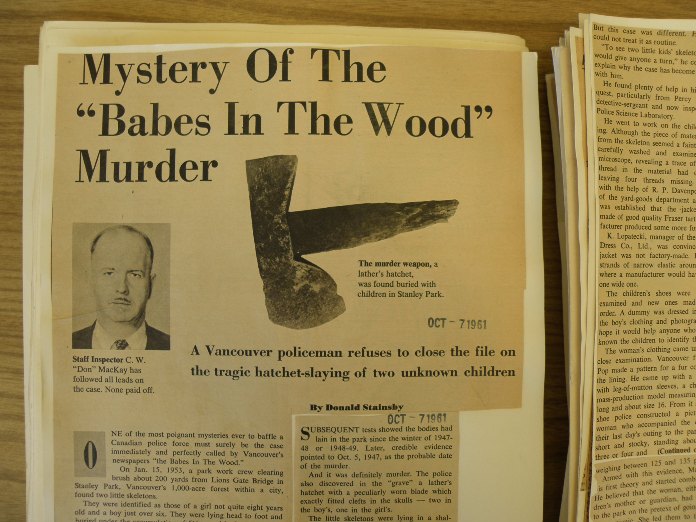

Stanley Park has a darker side. In January 1953, park workers made a gruesome discovery while clearing brush near the Lions Gate Bridge. They found two small skeletons. Tests would later show that these bodies had been there since the late 1940s. The murder weapon, a hatchet, was also found at the scene along with a woman’s fur coat, possibly belonging to the person responsible for the murders. Because of the clothing on the skeletons, it was believed for the longest time that they were of a boy and girl. It was not until the 1990s, that DNA tests proved that these remains were that of two boys. To this day, this mystery remains unsolved with no suspects, and the children have not been identified.

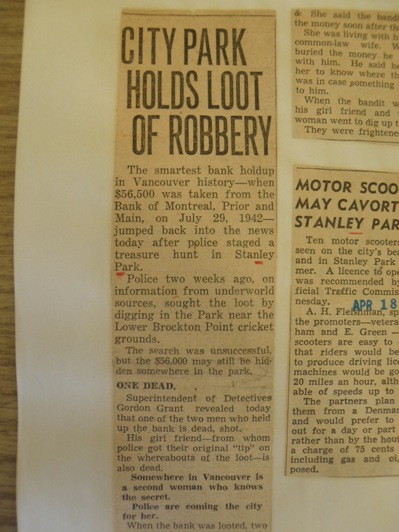

As you enter Brockton Point this weekend, it is possible that treasure is buried nearby, perhaps under the lower cricket field. In July 1942, two bandits held up the Bank of Montreal at Prior and Main and took off with $56,500. The money was never found. Three years later, police received a tip from what they believed to be an authentic source. One of the thieves had buried his share of $26,000 “in a clearing in a clump of trees, bordering the cricket pitch at Lower Brockton Point.” The informant was the girlfriend of one of the thieves who had been killed the previous year. She was with him when he buried the money shortly after the robbery. Park workers and police excavated the suspected area but could not find anything. There was never enough evidence to charge the suspects, and to this day the money remains missing.

Sports and Recreation

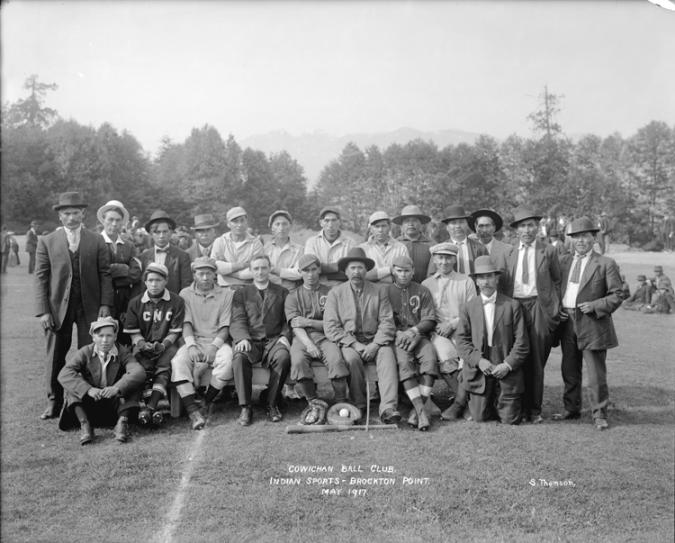

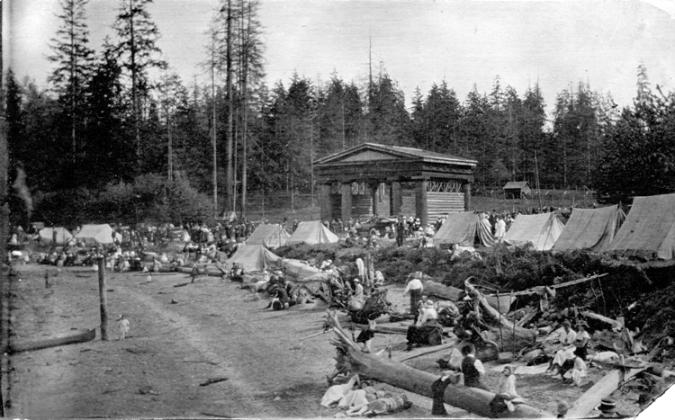

Brockton Point has been a sporting and recreational ground for almost as long as the city has been incorporated.

Stanley Park officially opened in September 1888. On Dominion (Canada) Day in 1891, the city saw the official opening of the Brockton Point athletic grounds. In the decades that followed, the Brockton Point grounds would become the city’s hub for sports and recreation. Thousands of spectators would gather to view sporting competitions from international leagues including cricket, lacrosse, field hockey, rugby, polo, lawn bowling and bicycle racing.

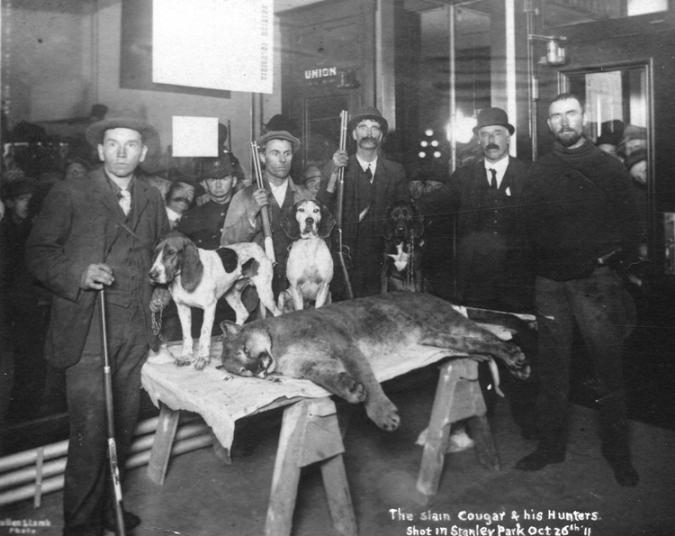

Wildlife

While the Brockton Point grounds were heavily frequented by the city’s residents, the depths of Stanley Park were still inhabited by wildlife, more wild than what we are used to today.

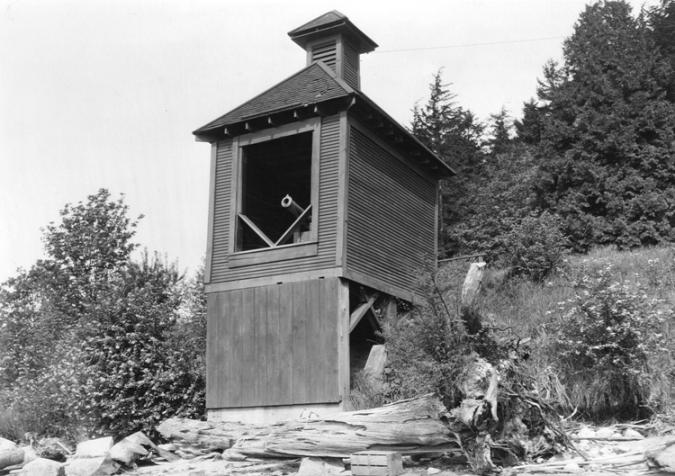

9 O’Clock Gun

Just south east of the Brockton Point grounds is Hallelujah Point, where you will find the 9 o’clock gun. Cast in 1816 in Woolwich, England, the cannon was brought to Vancouver and fixed not far from its current location in 1894.

The firing of the gun at 9 o’clock had a serious purpose. As part of his duty prior to 1894, William D. Jones, the lighthouse keeper at Brockton Point would manually detonate a stick of dynamite at 9 PM each evening for ship captains to regulate their ships’ chronometers. As the sound of the explosion would be heard at different times depending on where one was located in the harbour, captains would look for a flash in the sky. It was likely due to safety issues that the 9 o’clock gun replaced the procedure of manual detonation in 1894.

Burial grounds and a lost Squamish village

Prior to Vancouver’s incorporation, the area between the 9 o’clock gun and the Brockton Point lighthouse was the location of the city’s first cemetery. Many of the city’s first residents recall burying their family members in that vicinity in the 1870s and 1880s. Some members recall that it was also a burial ground for the Chinese and First Nations communities. It was by no means an official cemetery. Graves were not officially marked, and burials were not officially recorded. Matthews’ interviews could not determine the precise location of this burial ground, and by 1888 when Stanley Park officially opened, the park roads were laid down over this location. It is likely that many of the graves still exist under the roadway today.

When the road around Stanley Park was built in 1888, it is possible that the building material came from an excavation not far from the burial site. At the north western corner of the Brockton Point grounds is Whoi Whoi, which means “a place for making masks”. Today Whoi Whoi is known as Lumbermen’s Arch. In a letter to Matthews in 1932, archaeologist Charles Hill-Tout explains that Whoi Whoi was once the site of a Squamish Village. A huge portion of the grounds was at one point a midden consisting of layers of calcined shells and ashes. In certain areas, these shells went as deep as eight feet, suggesting that the midden could have existed for generations, even centuries, long before the arrival of European explorers. Unfortunately at the time, this material showed more potential for road building than having any archaeological value.

Stanley Park for generations has been the home for many First Nations communities long before the pioneers arrived. Whoi Whoi was just one of many communities. In her book, Stanley Park’s Secret, Jean Barman writes that even from the day of Stanley Park’s official beginnings in 1888, the park was considered a home and spiritual land to many members of the First Nations communities.

In the introduction to her book, Barman notes the only trace of these communities is a single lilac bush overlooking Vancouver’s Coal Harbour. If you walk along the sea wall and see the lilac bush, consider its age and what it has witnessed before and since the City of Vancouver’s beginnings 125 years ago.