This post was written by Kathy Kinakin, one of our volunteers.

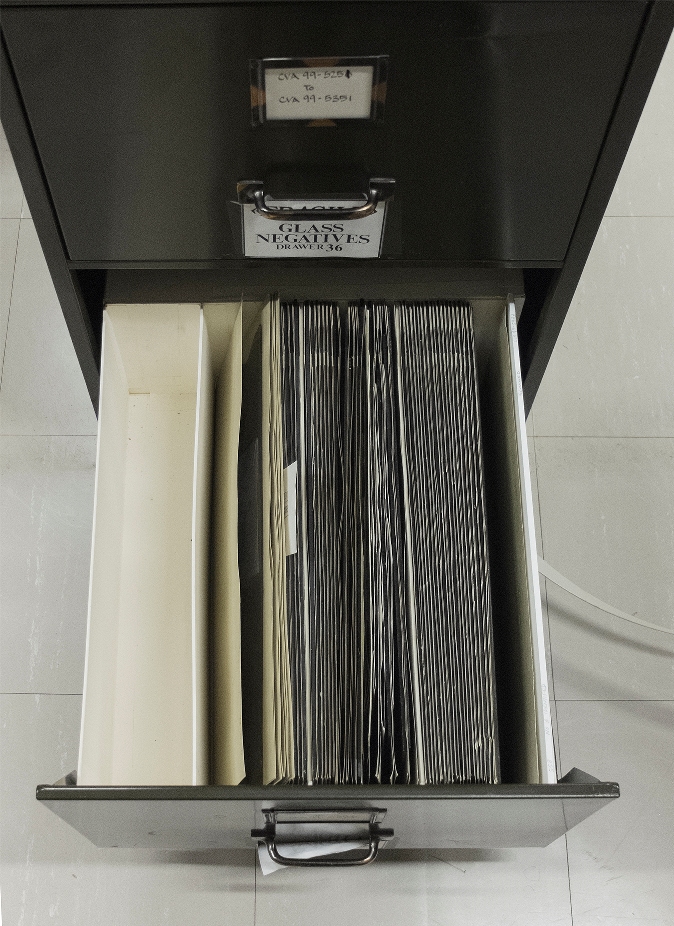

What to do when set to the task of rehousing of 335 17.8cm x 43cm panorama glass plate negatives stored in the drawers of a filing cabinet? The negatives are part of the Stuart Thomson fonds. Thomson was active as a commercial photographer in Vancouver for several decades in the first half of the 20th century. The negatives are large, very fragile and heavy, and because of their unusual size, the solution isn’t as easy as putting them in standard archival envelopes and an off-the-shelf archival glass negative storage box. In this case, a custom-made housing was necessary.

Glass plate negatives are normally safest when housed in envelopes and placed upright on their long edge in a storage box, as this protects the delicate surface of the negative from pressure. The size and weight of these negatives meant that only 7-10 of them could be put in a single box before it became too heavy to handle. A box like this would be quite thin and very unstable when sitting on a shelf so this was not a practical option. A larger, more stable box with spacers to securely hold the negatives could be used, though with the number of negatives needing to be housed, this wouldn’t be an efficient use of space. With all of this in mind, I decided to build a custom sink mat for each negative, and a custom clamshell box for a group of mats. The negatives would be stored flat, but with the support of the mats they would be well protected. I’d had some experience with this type of housing during my internship at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. There I made a sink mat for a 30cm x 60cm glass negative that was found loose on a shelf. The design seemed like a good solution for our panorama negative project.

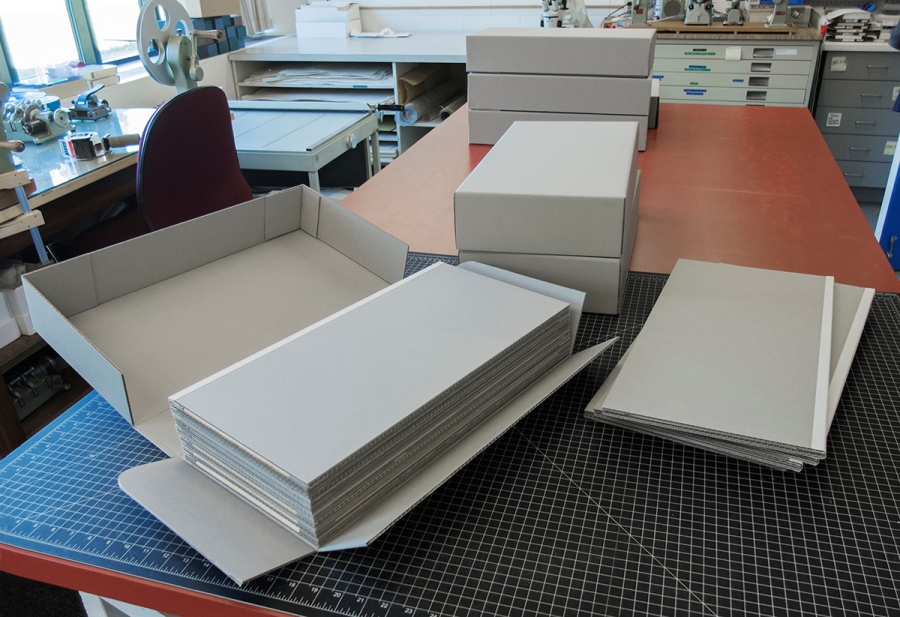

With a plan in mind, I designed the mats and the boxes and tried to estimate the quantity of materials needed for fabrication. Each negative would get its own sink mat with a hinged cover, and seven mats would be stacked together in a clamshell box for a total of 48 boxes. We decided that Perma/Cor E-Flute corrugated board would be the most cost-effective material to use for this project. It has the added advantages of being lightweight, easy to work with and available in large sheets which are perfect for creating custom designs. It has also passed the PAT (Photographic Activity Test) standard and so is considered safe to use in contact with photographic material. Gummed linen tape was used for hinging the mat covers and neutral PH PVA adhesive was used to construct the mats and boxes.

The first seven mats and clamshell box took almost two days to complete and looked a little rough around the edges. After some adjustments in the plans, and with help from the great people at the Archives who helped me figure out more efficient ways of mass producing all the parts needed for each mat and box, I was able to speed up the process and beautify the final product at the same time. By the time I got to the third drawer of negatives, I was able to make almost four boxes full of mats in two days.

Things slowed considerably when rehousing the last drawer of glass plate negatives as many were broken in half, or into several pieces. Broken negatives are usually housed flat in sink mats with pieces of mat board or corrugated board holding each section securely in place. This meant the broken negatives could be put in the same boxes as the others, making construction a little easier. Broken negatives need more space in the mat so that each piece of glass can be held slightly apart from the adjoining ones. Thankfully, the original size of the mats allowed for this expansion just by using thinner strips around the edges. With the broken negatives now also safely stored, the project was finally completed.

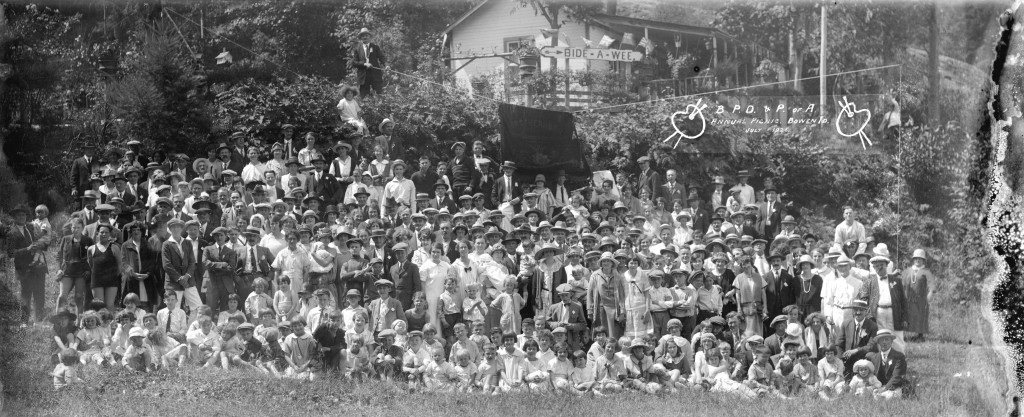

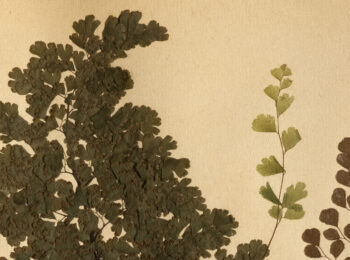

Sometimes people think that because a photographic object has been digitized and can be viewed in great detail on a computer screen, it isn’t really necessary to go through the effort and expense of housing and storing the original. Looking at the original object, whether a print, negative or slide, can be just as important as looking at the image. It can tell researchers a lot about the photographer’s process and create a context for the image that it might not otherwise have. The glass plate negatives that were so carefully rehoused for this project are a great example of the value of the material object. The photos below illustrate the difference between what you might see when viewing the digital file online and viewing the original object at the Archives.

It’s satisfying to know that these negatives are safely housed in their mats and boxes, waiting for researchers to study them.

Lovely post Kathy! I enjoyed it. Congratulations on finishing the project!

So that’s what your archival neg boxes looked like! Great article Kathy! 🙂

I really enjoyed reading your great post, Kathy! Very interesting and informative.