We have a specialized, custom-built freezer to provide the highest standard of care for the storage of our photographic materials. It was the first institutional freezer built to the specifications researched by the Smithsonian Institution and it was officially opened by Mayor Philip Owen on February 20, 2002.

Why a Freezer?

Some types of photographic materials are unstable and cold storage will prolong their useful lives. Storage at freezer temperatures will prolong their lives the longest.

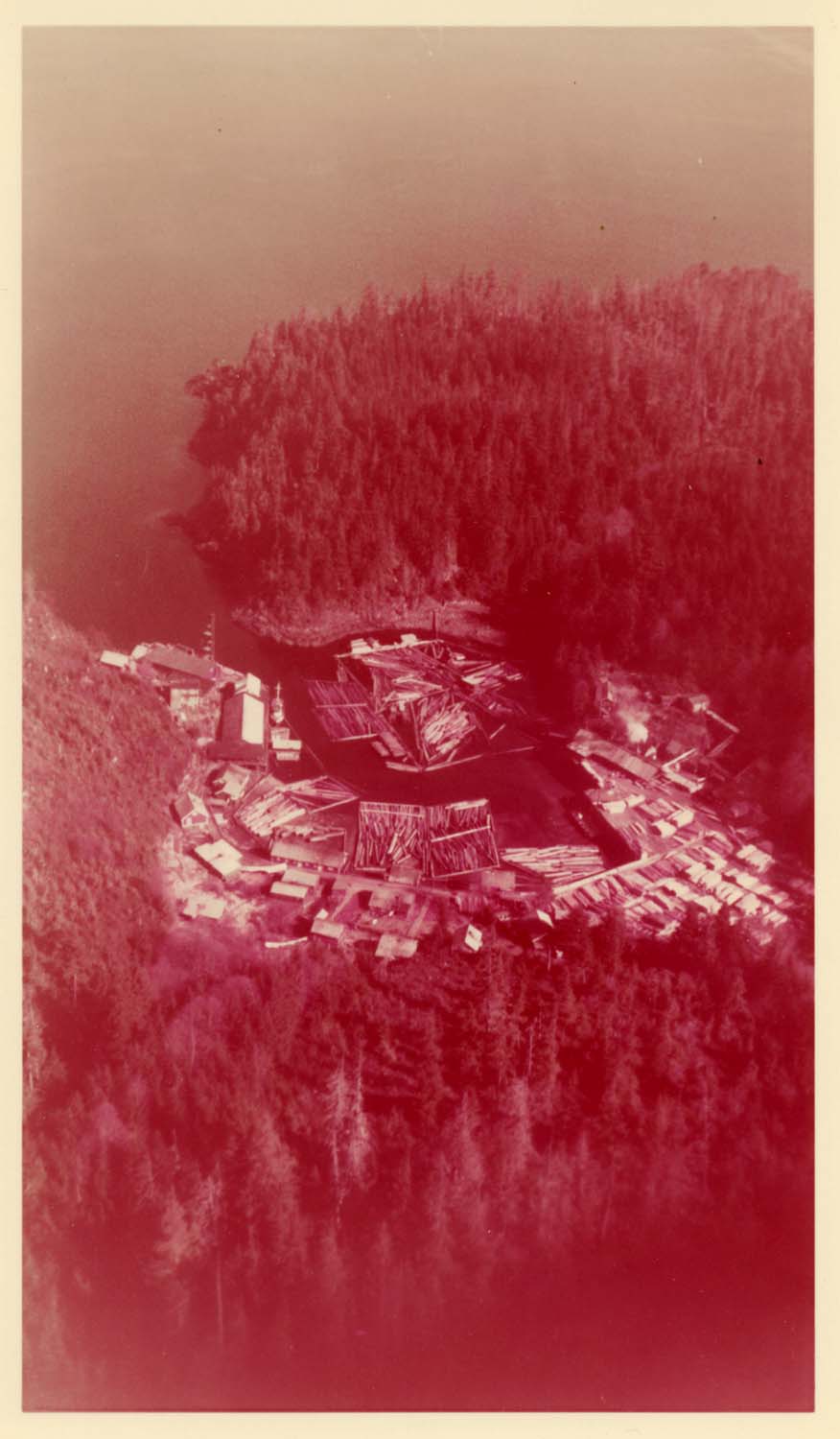

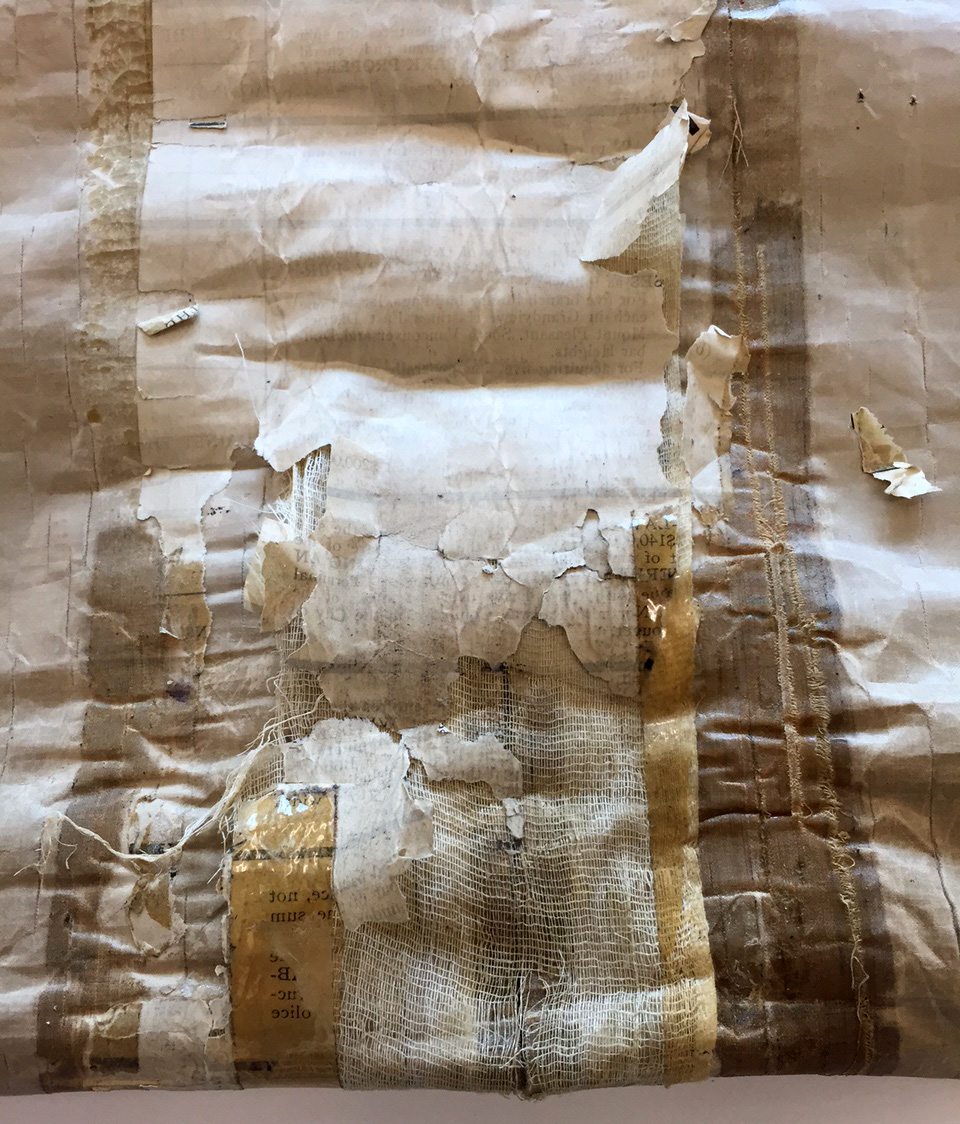

Without cold storage, cellulose acetate negatives wrinkle and become brittle

as they give off acetic acid (vinegar).

Colour photographs will fade, even when stored in the dark. Frozen storage will stop the colours from fading further.

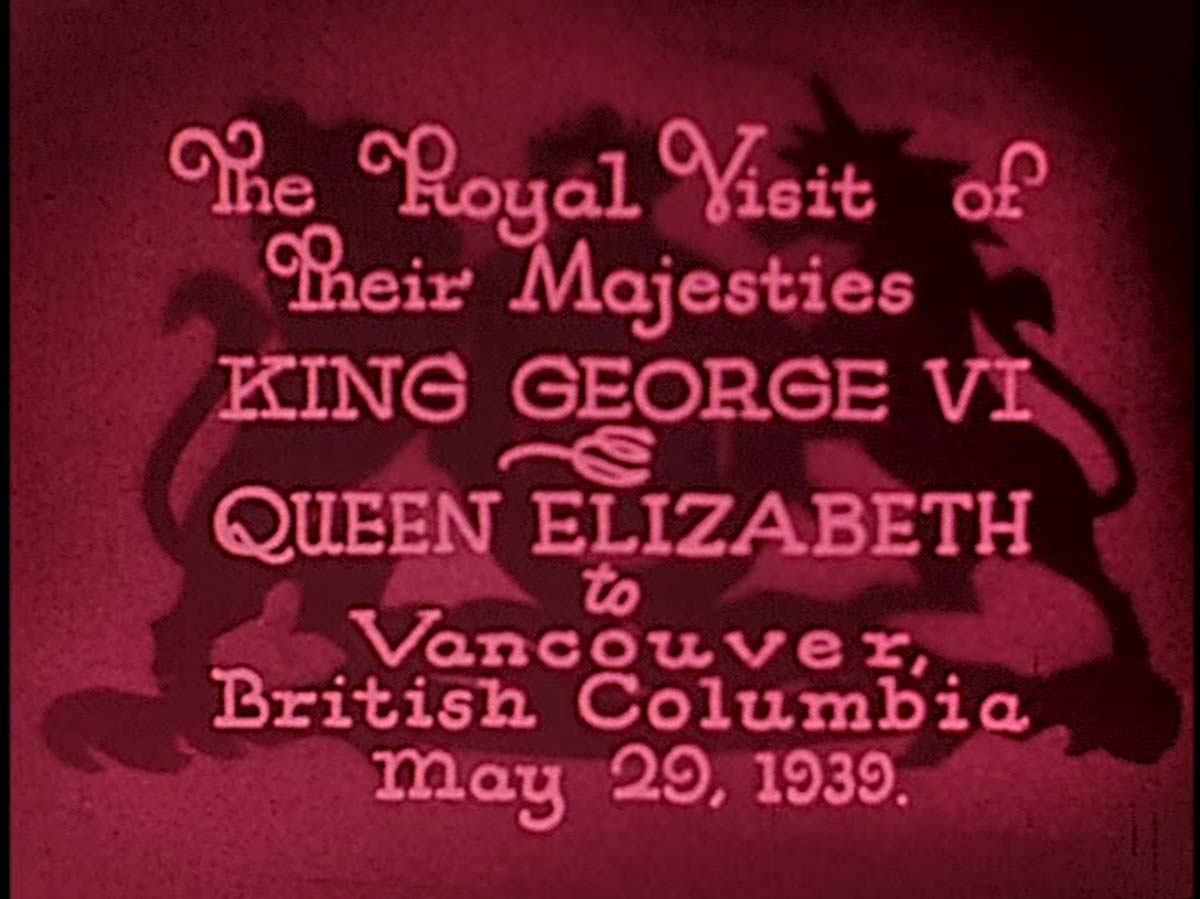

Movie films can have the same problems and will also benefit from frozen storage.

How big was our problem?

In 1995 and again in 1998, we surveyed our deteriorating acetate negatives using A-D (Acid-Detecting) Strips. These strips change colour to indicate how deteriorated the acetate negatives are, giving us a good idea how much time they have left before they become wrinkled. They were developed by the Image Permanence Institute for the motion picture industry and won an Academy Award in 1997.

We noticed that the negatives had deteriorated in the three years between tests and we counted about 113,000 negatives that should be frozen as soon as possible, with hundreds of thousands more that needed freezing eventually.

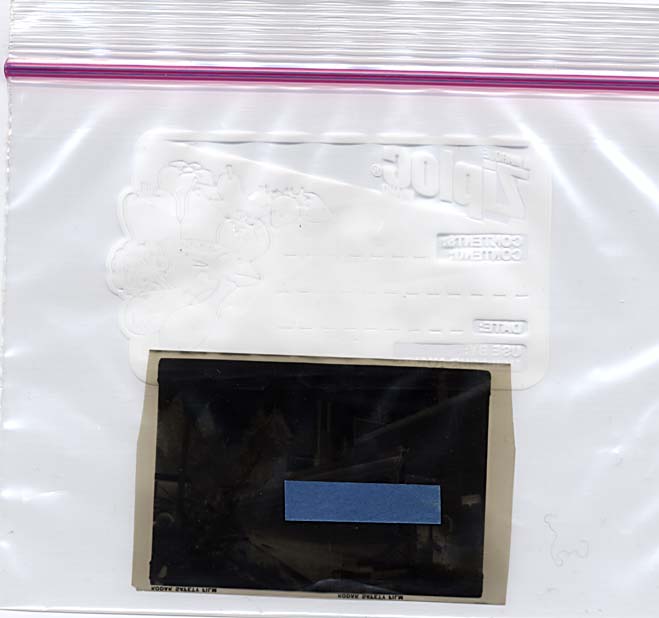

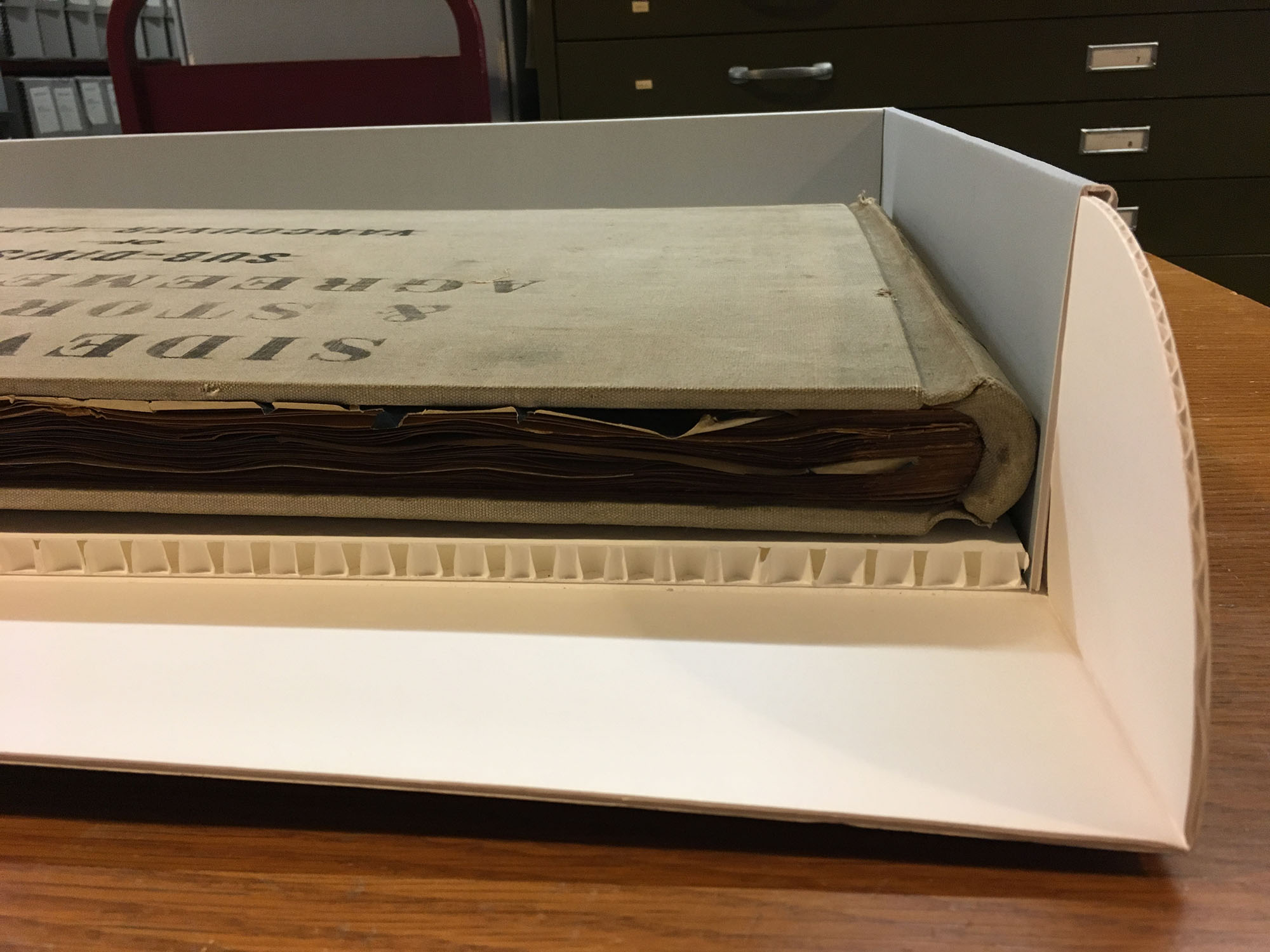

We packaged the high priority negatives in Critical Moisture Indicator packaging developed by the conservation research labs at the Smithsonian Institution and adapted by Betty Walsh of the British Columbia Archives. The packaging kept the moisture content of the negatives low by using two thick, sealed plastic bags, and pieces of dried mat board. The moisture content could be monitored using the small blue indicator square on one end.

The packages were created, assembly-line style, in a ventilated area to protect staff from the acetic acid given off by the negatives.

In 2000, the packages were boxed and driven to a cold storage facility in Port Kells which specialized in storing frozen food. They were secured on a pallet and stored on a high shelf in a quiet corner.

An hour down the highway, under layers of pallet wrap, corrugated plastic and packaging, access was difficult, but the negatives were safe.

OUR OWN FREEZER

We began to plan for our own on-site facility. The Smithsonian was sponsoring research into a low-cost and energy-efficient freezer that archives could use, and we discussed the design with them while the research was underway. Once it looked like the design worked, we built one.

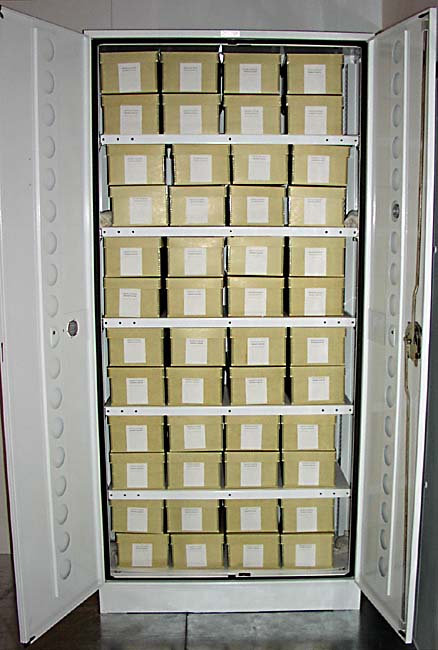

The Friends of the Vancouver City Archives raised funds to purchase the freezer. The freezer was built from an ordinary, modular walk-in freezer, as used by restaurants but with a couple of small changes to help keep the humidity low. It was built in 2001. After testing in early 2002, we brought our negatives back from Port Kells and put the boxed packages on shelves in the freezer in time for the opening in February 2002.

MORE EFFICIENT STORAGE

The Critical Moisture Indicator packaging was meant for small numbers (perhaps fewer than 20,000) of photographs, as a professional photographer might have. It’s not very efficient for larger volumes, as it involves freezing many layers of packaging—bags and mat board—which take up a lot of room in the expensive freezer space. We knew this, but we had to act quickly and there was no other reliable way of packaging them at the time.

Fortunately, the Smithsonian was also researching a storage method that could store photographic negatives safely and with minimal packaging. Storage cabinets with gasketted doors were put into the freezer. The shelves were lined with mat board and half a kilogram of dried silica gel was placed in each cabinet. The photographs could be stored on the shelves in their regular archival boxes, without extra plastic bags. We were able to get 50,000 negatives into the first cabinet we filled.

Traditionally, cold storage for cultural materials uses active dehumidification systems, which means they not only have an electrical system that controls temperature, but a separated electrical system that removes humidity from the cold air. Active dehumidification systems are

- expensive to purchase and install (especially at temperatures below zero)

- fussy to maintain (requiring HVAC engineers to adjust)

- require about four times the electricity to achieve the same humidity at freezer temperatures

The passive dehumidification system we use, which combines the freezer design with the gasketted cabinets, is

- inexpensive to purchase (some mat board and silica gel)

- easy to maintain (regular maintenance calls and the easy task of drying of the silica gel)

- green in its energy consumption

Today, the freezer holds approximately 750,000 negatives, colour slides and films. We still receive inquiries from around the world on our experience with this successful project.

Download a detailed, illustrated account of our work to provide cold storage for photographs at the Canadian Council of Archives web site.

Great article – it gave me shivers reading it.