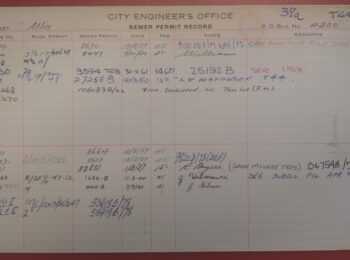

The final part of hunting for information about 2116 Maple Street, after looking at fire insurance maps, water records, building permit registers, and photographs, involves looking up the names of the residents in the city directories.

The city directories are one of our most well-used resources, as many researchers look for the history of a building’s occupants, or where a relative lived over time. It is time consuming to go through the publications year-by-year and trace the occupants of a house, but, I would argue it is time well spent. Often an underlying narrative emerges about the residents, about the house, and about the neighbourhood.

The mechanics of using the directories are fairly straightforward. They are divided into two major parts – addresses and names – also with a third section for advertising or business listings. However, before we get into the how-to, I want to step back and look at the history of the directories, what other information they contain, and why I even started thinking about these things in the first place.

Until recently I approached the directories more as the place to go to find occupants of a building, but as I spend more time using them, I have been realizing that they contain a wealth of information in addition to people’s names and addresses.

As George Young wrote in his 1988 The Researcher’s Guide to British Columbia Nineteenth Century Directories, “Directories constitute one of the most detailed, diverse, and occasionally, even delightful insights into our past.”[1] And so I started looking at every directory from 1888 to 1996 to see what I could learn about them – publication times, how the information was collected, who published them, and what other information they contained.

Many of the early directories I could surmise the month they were published through the dates written at the bottom of a preface or in the introductory material. Some directories were published in January, while others were published in April, May, or June. By the 1940s prefaces with dates were no longer written, but dates could be found under the governmental information, with a phrasing like, “Latest information available October 27th, 1945” in a 1945 BC and Yukon directory, or, “elected June 12, 1952,” in a 1952 Vancouver and New Westminster directory giving some frame of reference. By the 1960s those phrases disappeared, however, and with it an indication of the time of year a directory was published. It is important to remember, though, that the information in the directories was typically collected in the year leading up to the publication date.

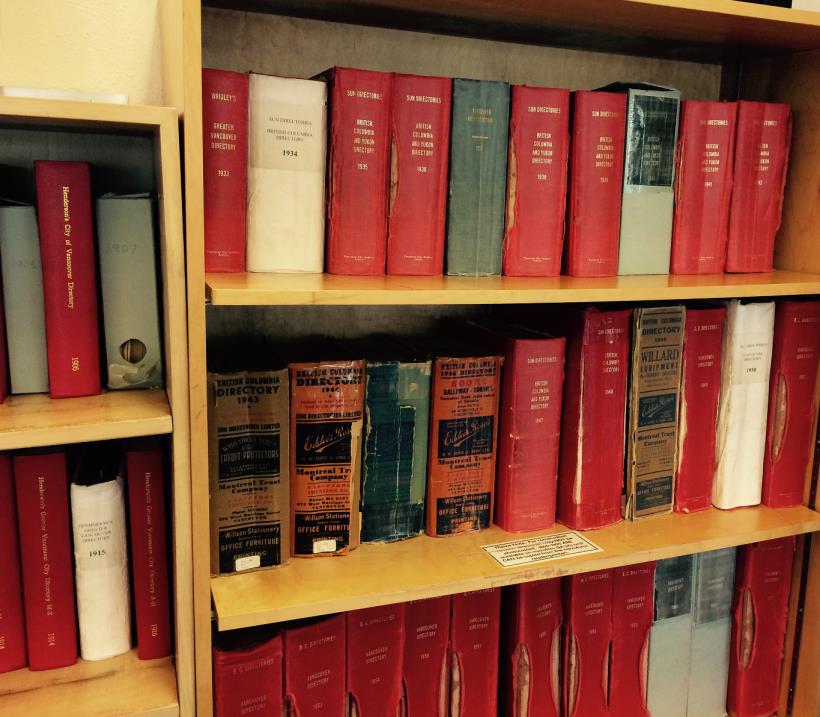

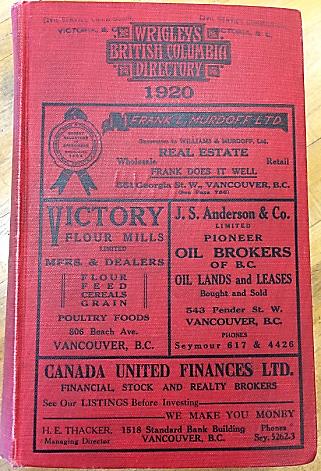

The publishers of the directories changed throughout the years. The first Vancouver city directory was “Compiled for R.T. Williams by Thomas Draper”, and published by R.T. Williams in Victoria. Henderson’s City Directories started appearing soon after. The preface and introductory material of these two different directories were keen to point out the advantages of using their particular directory over the competitor’s, in phrases such as, “Every effort has been made to secure the christian [sic] names in full, which we believe will be of advantage,” in Henderson’s 1890 directory, and “There are one hundred pages more than were in the 1889 Directory; while the price remains the same,” in Williams’ 1891 directory, or, in the case of Henderson’s 1919 directory, “The Miscellaneous Section in the front part of the volume, containing up-to-date statistics and information, much of which is not to be found elsewhere in print”. Wrigley Directories, Limited, began publishing its directories in 1918, and eventually amalgamated in 1924 with Henderson, while Williams’ directories for Vancouver disappeared. For the next ten years, Wrigley’s dominated the directory publishing scene in Vancouver. Sun Directories Limited bought Wrigley’s and started publishing their version of the directory in 1934 [2]. By 1950, the city directories were being published by B.C. Directories, Limited, which eventually became a division of R.L. Polk & Co. Ltd. Publishers in 1972. The directories were only published as long as they were profitable. As other information sources became available, the directories ceased publications in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

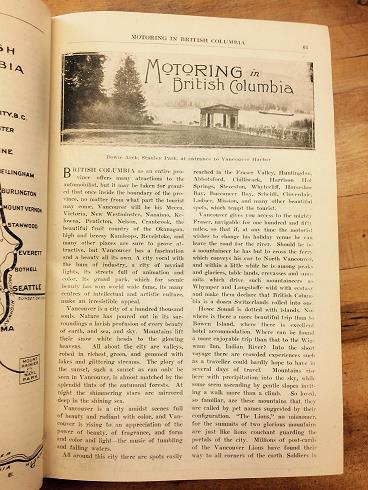

Spending time going through the directories for dates made me aware of the wealth of supplementary material crammed into the front matter. The Williams’ 1892 directory has a summary of the number of days snow fell in Vancouver, and number of “fine days”. Williams’ 1893 directory has a list of general wages for labourers and the hours they work, customs statistics (amount of imported and exported goods), and postal rates. The 1909 Henderson’s directory added a Chinese business firms directory, as well as a breakdown of the demographics of Vancouver’s population into general ethnicities. A 1911 Henderson’s has listings of lighthouses, light keepers and their mailing addresses, along with school statistics. When Wrigley’s took up the publishing city directories, it furnished the fronts of its directories with descriptive sections with accompanying photographs titled “Sport in the Canadian Pacific Rockies”, and “Motoring in British Columbia”.

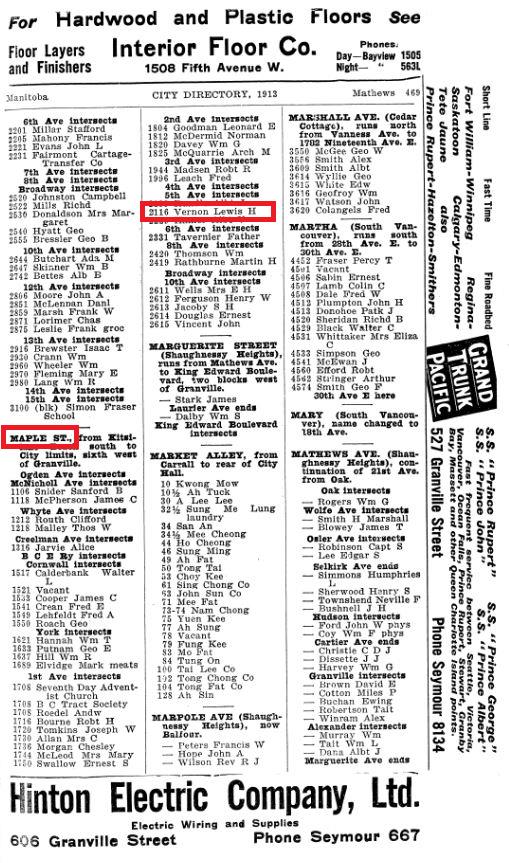

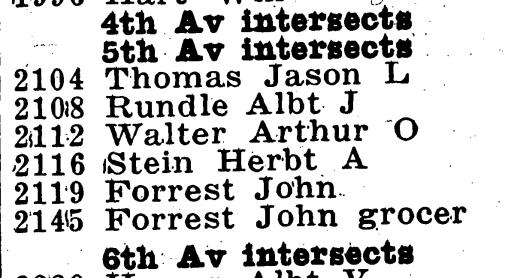

Now that I have taken a detour, let me get back to explaining how to use the directories by returning to my house history hunt for 2116 Maple Street. From the water service records and building permits, I know that the house was built in 1912. However, it does not show up in the city directories until 1913. Often, it is the case that a house or building will not start appearing in the directories until a year or two after it was built.

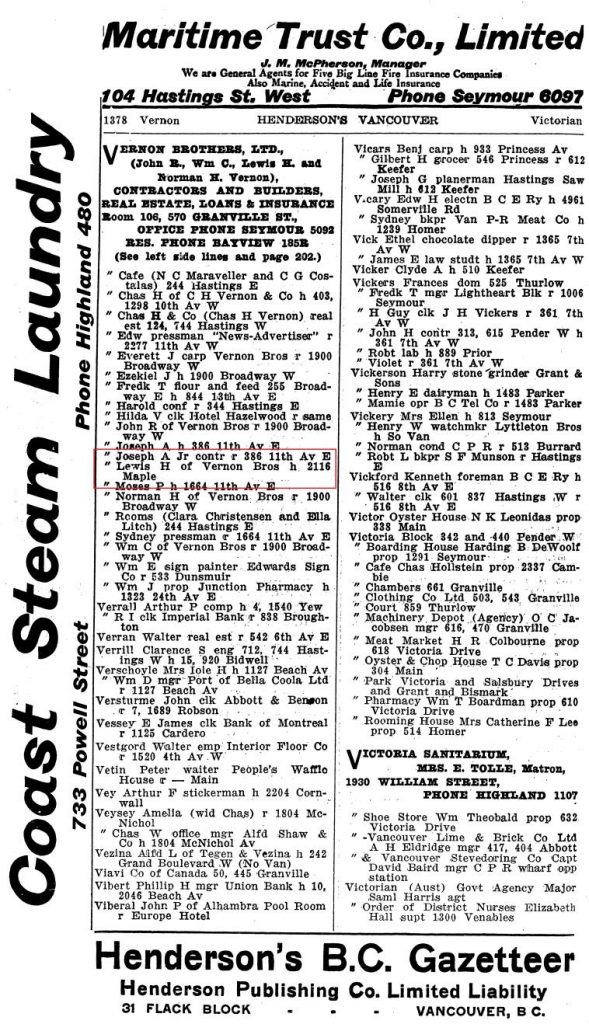

Since I am looking up an address, I begin with the address section of the directories. In the 1913 directory, the occupant is listed as Lewis H Vernon. After I have the name, I then turn to the name section of the directory.

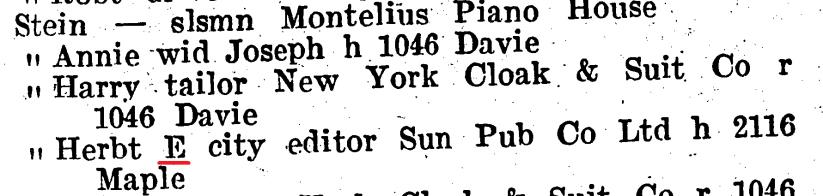

From looking up Mr. Vernon’s name, I see that he works at Vernon Brothers Ltd., which, very nicely has a listing at the top of this page, detailing that Vernon Brother Ltd. was in the business of contracting, building, real estate, loans and insurance. It also lists the office’s address. When looking up the name, I will know I have the correct one because the house address is listed next to the name. I find this a good way to double check my research work.

I will then repeat this process for the proceeding directories – start by looking up the address, noting the person or persons listed, then look up the person or persons to give me information as to what their occupation was. It is important to remember that the listing of occupants is not exhaustive. In the early directories, women (unless single or widowed) were not typically listed. This changed by 1934 under the new publisher Sun Directories Limited when married women were listed in parentheses after their husbands’ names. The directories also only capture adult occupants. Furthermore, people from ethnic minorities were sometimes listed simply by what nationality they were, or that the canvasser assumed they were, rather then named.

When I look through the directories I keep in mind that there may be inconsistencies or errors. The information was collected by door-to-door canvassers, and later in the 1990’s telephone canvassers. The information was given voluntarily and misspellings could occur. For example, from the 1916 directory, the occupant’s middle initial appears differently in the address section and name section.

Abbreviations are found throughout the directories including for names, businesses and occupations. A page is typically included at the beginning of the directory that helps decipher them.

Over the years a civil engineer, a phonebox operator, a university student, and a fisherman lived at 2116 Maple Street.

The more I do house history hunts, the more I become addicted to it. I learn more about how this city developed, who the inhabitants were, and gain a better appreciation for why certain features exists. For instance, why a road curves a certain way, or why a building, though now residential, looks like it once was a corner store. House history research is both a good way to be introduced to the Archives and the types of records in our holdings, and can spark one’s curiosity about the past.

[1] Young, G. The researcher’s guide to British Columbia nineteenth century directories. University of Victoria, 1988.

[2] City of Vancouver Archives, Wrigley Printing Co., AM54-S23-2–, Loc. 505-E-04, File 253, Conversation with Roy Wrigley written by J.S. Matthews, 24 April 1947.

Editor’s note: A number of institutions in the Lower Mainland hold partial to full sets of City Directories, either in hard copy or on microfilm. The digital versions linked to in this post are part of the Vancouver Public Library’s BC Directories collection dating from 1860-1955.

Why not past 1955 for the VPL set? Surely they would, or should, have extended the scanned collection to the 1970s by now.

By the way, your ReCAPTCHA security program is overbearing and tedidous.