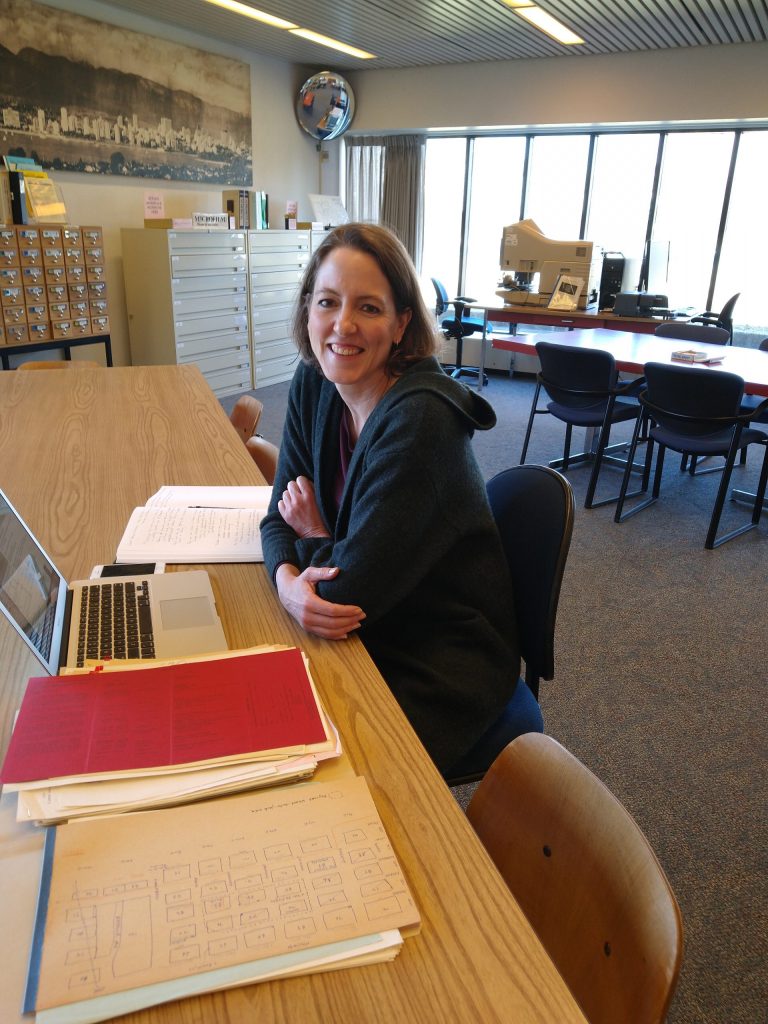

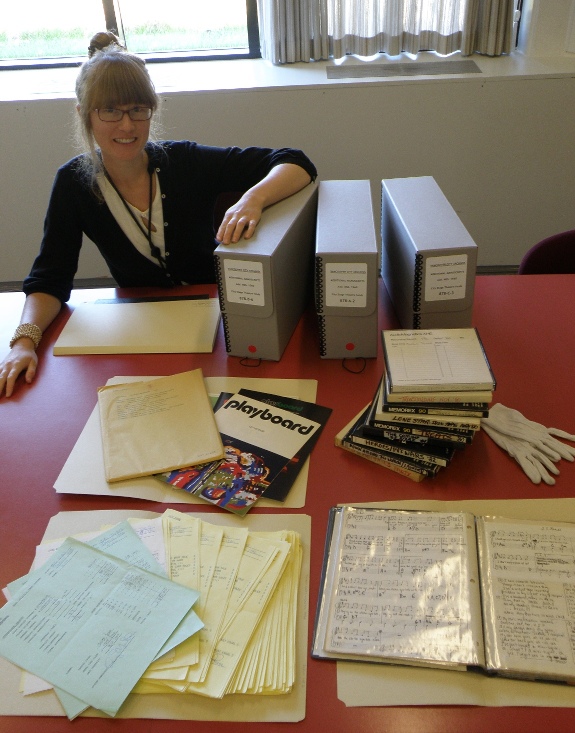

Jennifer Chutter is a PhD candidate in the interdisciplinary cohort of the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University. The working title of her dissertation is “Palimpsests and Place-making: An exploration of Strathcona as the idea of home”. Jennifer has been visiting the Archives for her dissertation research with a focus on analyzing both City records and the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association fonds (AM734). This blog piece is a summary of an interview with Chutter conducted in early March 2020.

Tell us about your project

I am drawing on the idea that neighbourhoods have layers and that you have to kind of peel back the layers. There are layers of municipal history and personal histories that are embedded into a landscape and I am interested in how these layers interact, overlap, and work together. The emergence of the Strathcona Property and Tenants Association (SPOTA) is really interesting because the residents were challenging what we would now call the colonial structures that are embedded into the landscape. The layout of that neighbourhood is based on very late 19th century Victorian English ideas of how people should live in houses: the land was surveyed, a specific style of house was built and by-laws stipulated how residents could use their houses; with the expectation that they would be used by nuclear families and not take on boarders, rent rooms, or have any extended family living with them.

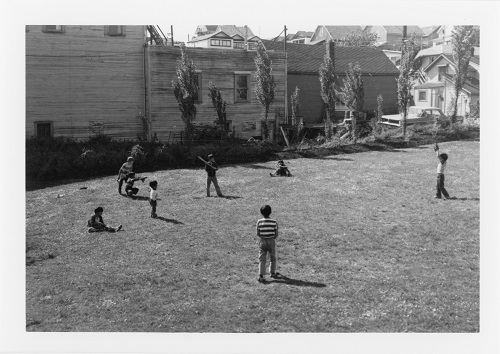

By advocating that their neighbourhood and housing should remain, the residents pushed back on that narrative of domesticity and the idea in urban planning that the best way to house low income people was through public housing and the subsequent regulation of their space even further. The impending demolition through urban renewal meant that residents would lose their ability to supplement their income through work from home or room rentals if they were forced into public housing; it meant more limited space to have hobbies; and kids living in the neighbourhood lost their park – because the park was expropriated to build the McLean Towers public housing. The residents successfully fought back the City of Vancouver’s urban renewal schemes.

My research focus is from 1967 to about 1977 predominantly, because that was the biggest buffer of change. However, there was a study done in 1950 of the neighbourhood that became very foundational in declaring the neighbourhood ‘blighted’ and putting in plans for renewal. There were two renewal projects that were completed in Strathcona before SPOTA successfully organized: Raymur Public Housing and McLean Towers Public Housing.

SPOTA and the Strathcona neighbourhood

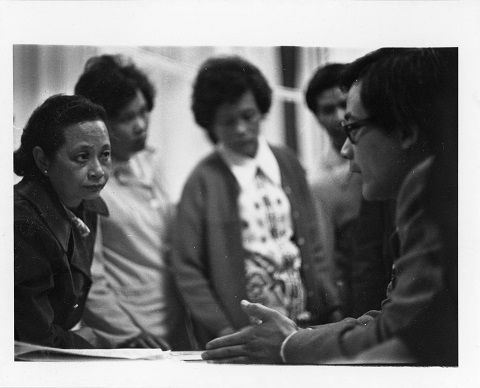

The neighbourhood turnout for SPOTA to represent resident interest was very high. SPOTA recognized that communication was the biggest issue. The City wasn’t communicating to the residents. Residents felt that decisions were being made above them without consultation. So they organized block captains, going door-to-door, and they went in pairs to make sure they had a translator so that if a resident spoke Portuguese, Italian, mostly Cantonese, they would hear what was going on in their neighbourhood in their own language. By mid-December of 1968 they had done all this door-to-door knocking and had over 600 people show up to their meeting and that’s when SPOTA was established.

A photographic print taken by SPOTA showing a group of kids crossing the street at MacLean Park. Reference code: AM734-S4, 175-A-02 fld 05

Another key recognition was the need for lawyers to support them and to understand zoning and by-law regulations because that influenced what they could do with their space. It’s quite fascinating that a group of volunteers figured out ways to navigate three jurisdictions of government (federal, provincial, municipal) to decide on housing levels that were inclusive. SPOTA also operated with tenants and homeowners considered equal voting members in the neighbourhood.

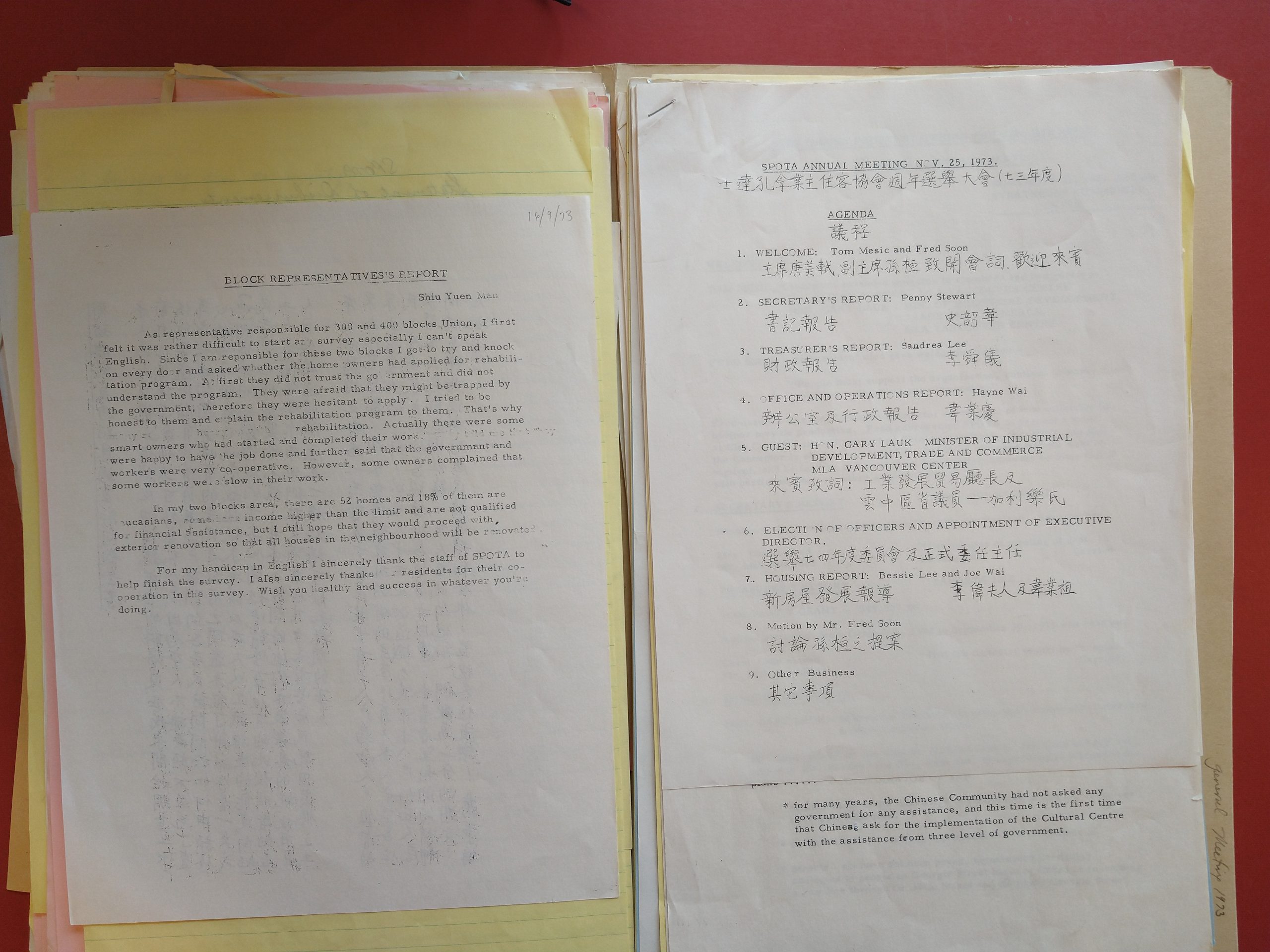

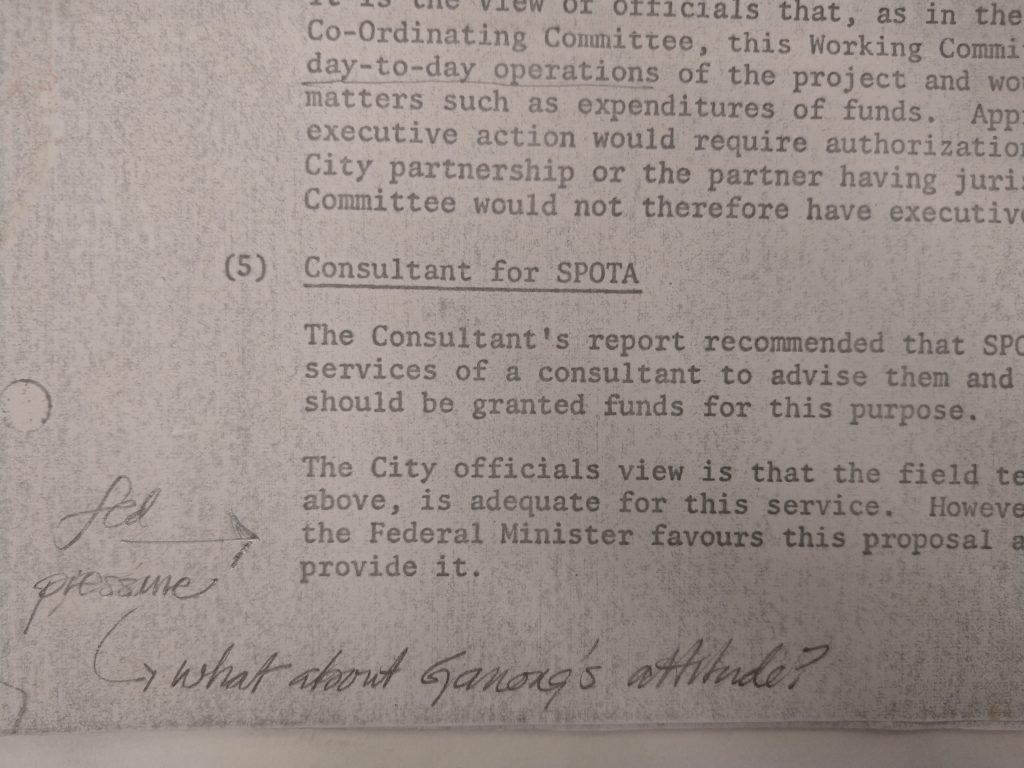

Analyzing government records & records of a community organization

A challenge in looking at both City records and the SPOTA files, which are very different, is to pay attention to who’s writing the document because that “voice” is not always transparent. [Authors] would have come with their own personal histories, personalities and agendas and it can be hard to kind of tease that out. More so in the City records because those are typically typed with no marginalia. Whereas, in the SPOTA files, there will be a typed City document and someone else will have gone through it, underlining or commenting on sections and “talking back”.

It’s easier to figure out how SPOTA was responding to an issue but City records often don’t have that kind of notation and it can be harder to engage with in the same way.

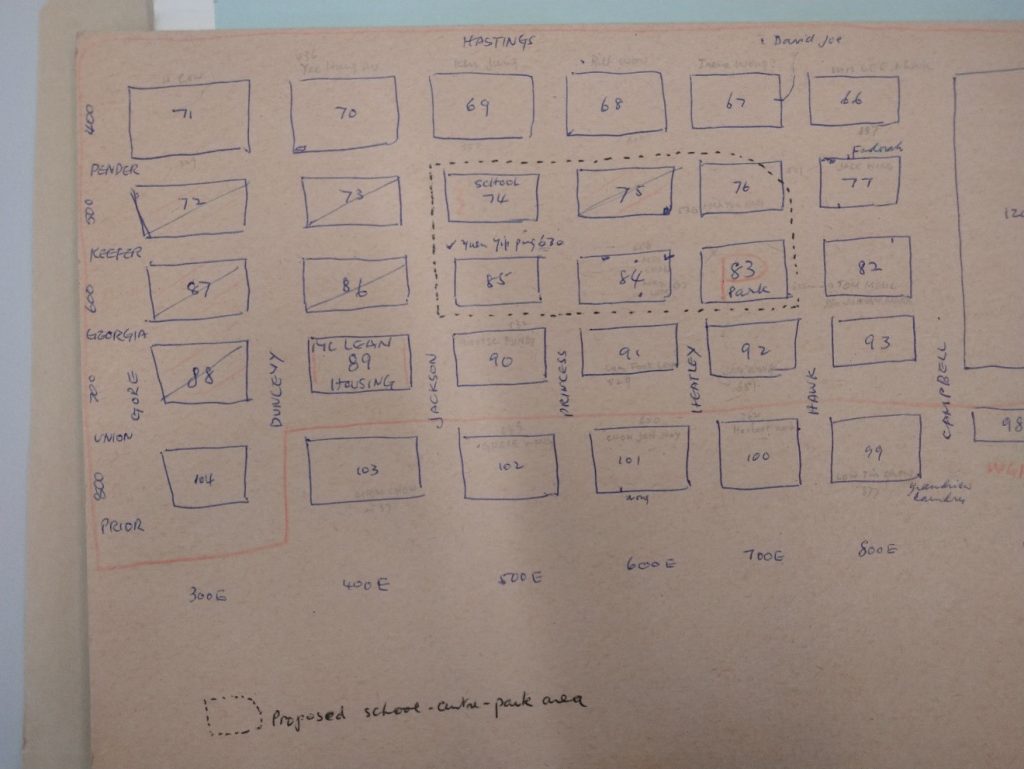

SPOTA Maps

My research project will also be incorporating a digital mapping component. The residents of Strathcona used maps in really interesting ways to advocate for their sense of home and place. They created their own sets of hand-drawn maps and I am recreating those to show that there are multiple ways to map a neighbourhood, which was essentially what SPOTA was arguing. Rather than just structures, their maps included details such as people’s names, a person’s history of living in that neighbourhood, their cultural background, and whether they wanted to stay in Strathcona or not [amidst urban renewal].

Cities will naturally grow and change and Strathcona residents acknowledged that; they said, ‘We’re not saying that we don’t want to improve things. We’re asking can we do it in a way that makes sense to the people living in this neighbourhood right now to ensure that nobody gets displaced’. There are bigger ramifications, it’s not just about moving to a new house. It’s all the tendrils of your life that spread out from the house that tell you this is home.

Our thanks to Jennifer Chutter for generously giving us some of her time to talk about her research. We’re looking forward to seeing the results of her work, including its digital mapping component.

Excellent information and facts. Only real difficulty I was basically receiving was viewing the pics. No idea exactly why.

Hello Dan. If you mean you’re not seeing images once you click on the link in one of the post’s captions, that’s because the link is taking you to our database descriptions of items that are not yet digitized. All there is to see is the information about the images (such as creation dates, scope notes and the ID of the box or folders they are contained in).