The Archives is pleased to announce we have a new guest exhibit on display in our gallery. Curated by Camryn Traa, “Otter Moments” explores the strange and sometimes surprising connections between sea otters and Vancouver. Traa is an undergraduate student in the History Honours program at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and created this exhibition project during her summer internship at the Archives in collaboration with the UBC Department of History’s Public History Internship Program. This is the first in a series of posts about her project.

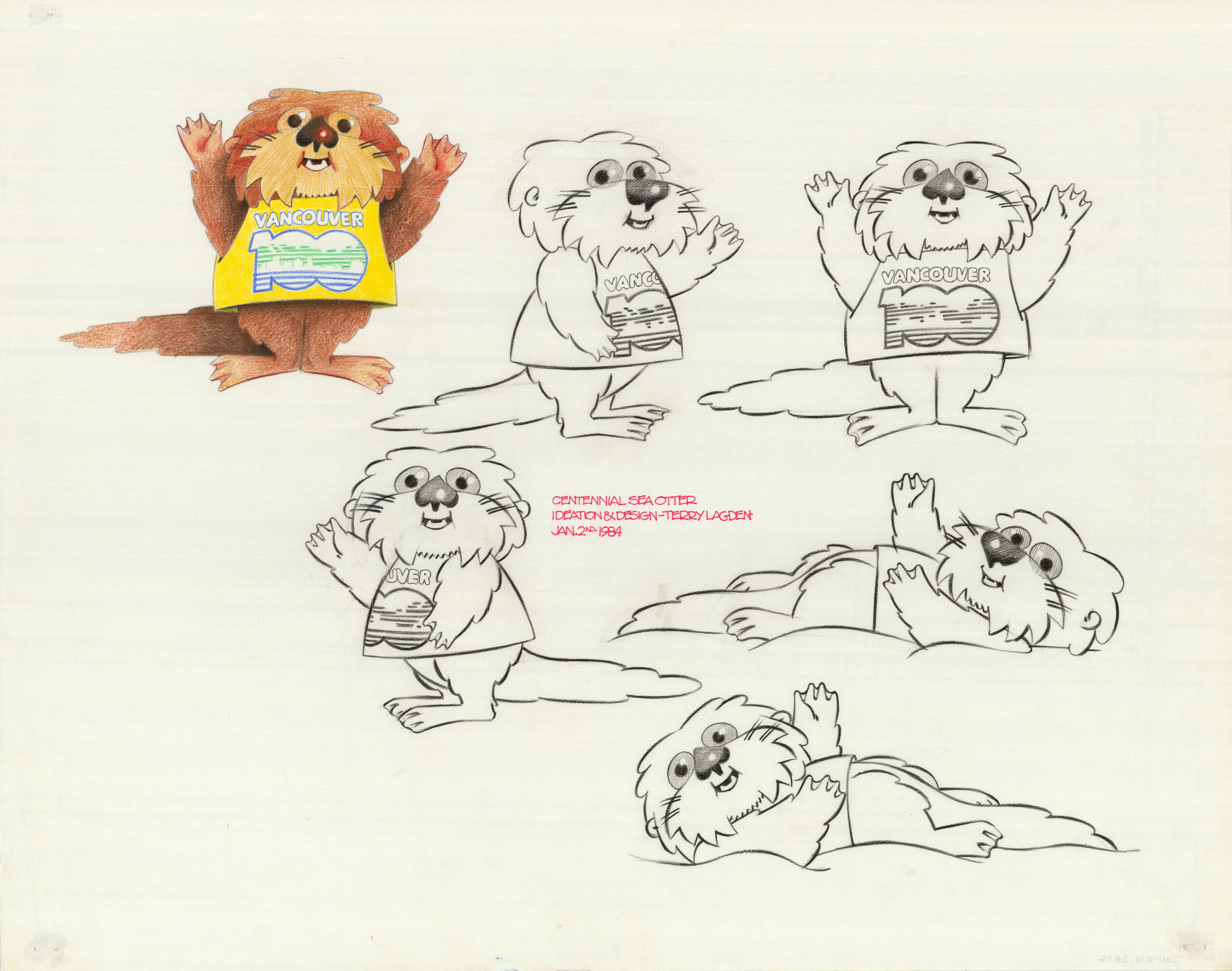

In 1986, Vancouver turned 100 years old and made a splash on the world stage by hosting Expo 86. Preparations for such a big occasion took time, and the Centennial Commission began planning special programs years in advance to celebrate the City’s 100th anniversary. In 1984, the Commission’s Communications Department, led by Doreen Maruska, created a mascot for the city. They chose a male sea otter––described as fun-loving and resourceful––to represent Vancouver. This may seem a surprising choice, however, given the fluffy creatures never actually lived in the waters around the city.

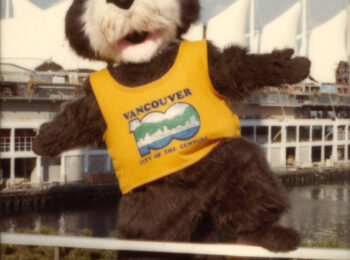

After the Centennial Commission announced the city’s mascot would be a sea otter, they mounted a “Name the Centennial Otter” contest. Nearly 350 names were entered and from them ‘Tillicum’, submitted by the Paint family, was chosen. Runners-up were Teeter T. Otter, Nootka, Splash, Skookum, High Tide, Bunsby, Stanley P. Otter, Otta C. Vancouver, Centy, and Abalone. The Tillicum mascot costume was designed, built, and introduced to the public in 1984. Mayor Mike Harcourt and BeeBop Beluga, the Vancouver Aquarium’s mascot, welcomed Tillicum at his first public appearance at the Aquarium on August 16, 1984.

‘Tillicum’ is a Chinook Wawa or Chinook Jargon word with multiple meanings, including friend, people, and relations. Chinook Wawa was a pidgin language that borrowed from the languages of multiple Nations, and later French and English. It was used for trade along the West Coast until the early 20th century.

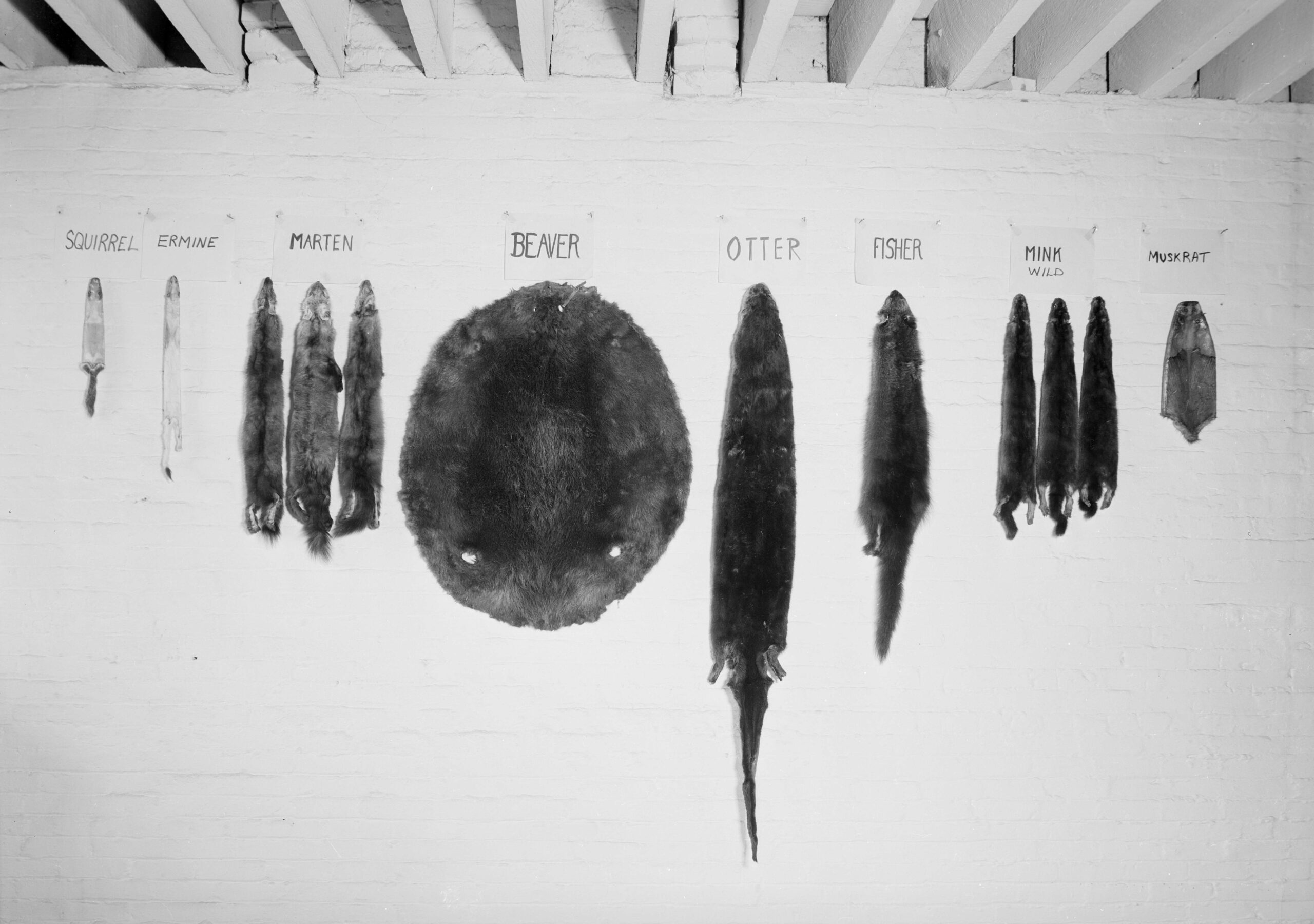

But why did the Centennial Commission choose a sea otter to be Vancouver’s mascot? They made this decision because they felt the sea otter played a star role in the history of the province. Sea otters have the thickest fur in the animal world. While most marine mammals have blubber to keep themselves warm, sea otters have only their extremely dense fur and fast metabolism to help them survive. Their pelts understandably played a large role in trade amongst First Nations and were used as status symbols for chiefs and people of high standing. Sea otters’ fur likewise made them incredibly attractive for European fur traders. In the 18th century, Russian explorers and later the British Captain James Cook brought news to Europe of the abundant sea otters along the coast––and their valuable pelts. This inspired European interest in the northwest coast of North America, eventually leading to the colonization of the region known to settlers as British Columbia.

During the height of the early 19th century Pacific maritime fur trade, sea otter pelts sold for anywhere from 3 to 10 times the price of a beaver pelt. Unfortunately, sea otters paid a steep price for their valued thick fur coats. By the early 20th century, the population had declined from a high of over 100,000 to fewer than 2,000 worldwide. In British Columbia, sea otters disappeared entirely.

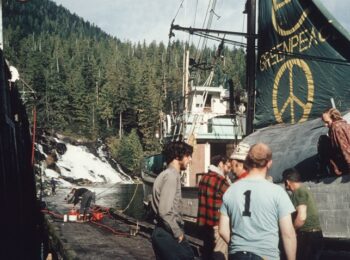

In the next post, we’ll explore sea otters’ return to the coast of British Columbia, and their interesting ties to Greenpeace and nuclear testing. Stay tuned for Part II!

Editor’s note: The Archives’ gallery at 1150 Chestnut St. in Vanier Park is open Monday-Friday, 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM. We encourage you to check out the exhibit in person!